You could do worse, as law enforcement in a superhero universe, than putting everyone on a watchlist who’s ever publicly proclaimed “I’ll show ’em! I’ll show ’em all!”

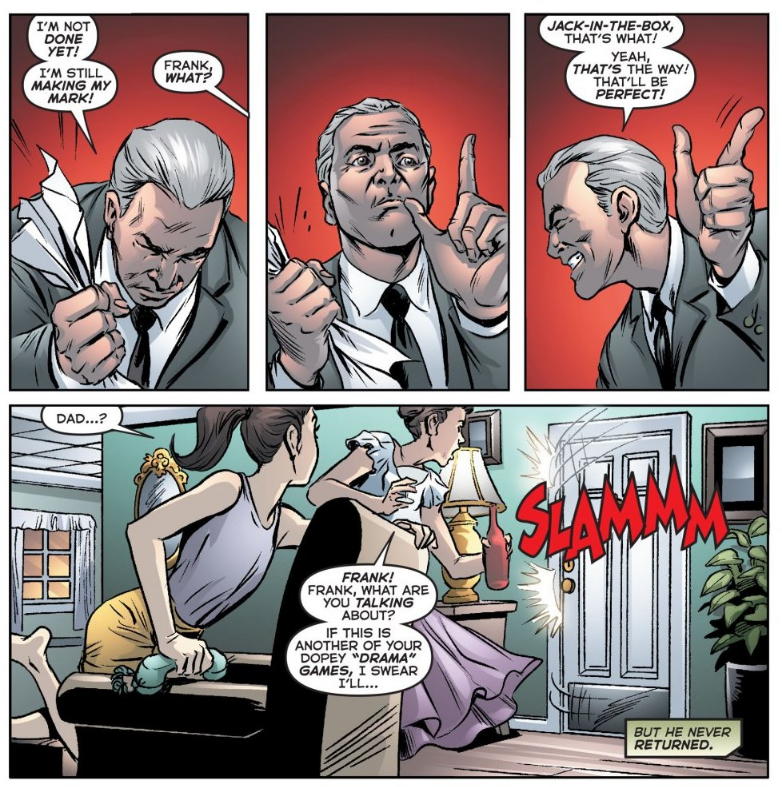

This half of the Jack-in-the-Box concerns the 1960s supervillain Mister Drama, whose origin is that he was rejected from a Shakespeare play because he didn’t have enough fire in his belly. Inevitably he shows them, he shows them all, the best way he knows how – becoming a themed supervillain and mobster.

It’s kind of the perfect pairing – the supervillain who’s half smiling and half scowling, versus the hero who’s always got a happy face on, both embodiments of the fundamental theatricality of superheroics. If anyone in this comic ever mentioned JSOC the whole thing would collapse in on itself – anything that self-serious would be like poking a balloon with a match.

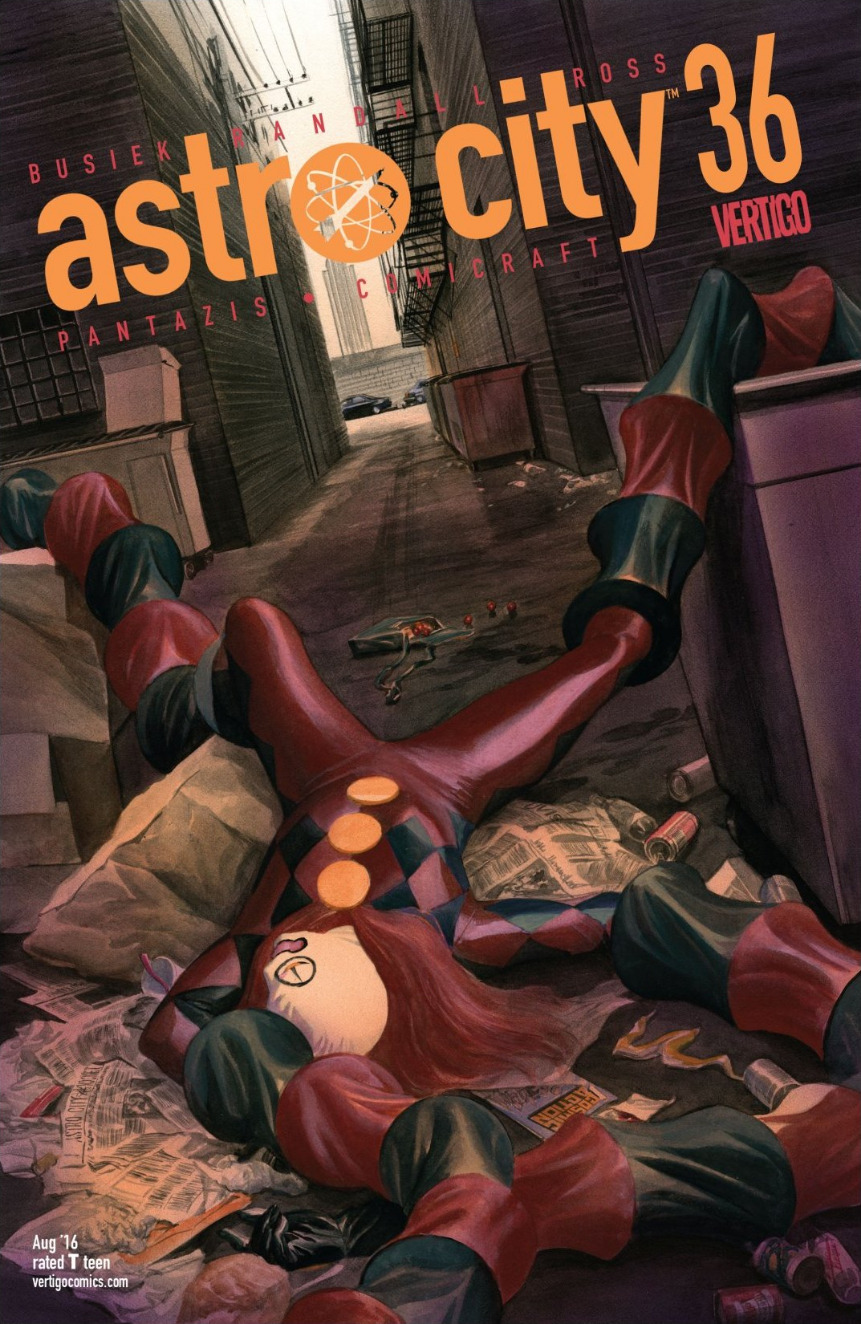

Of course, Mister Drama is kind of an inferior name to “Drama Queen,” who is the villain that Jack-in-the-Box and the extended JITB Family are facing, and she too, is a legacy – the classic kind of supervillain, the kind who’ll spout that other watchlist-worthy line, “we’re not so different, you and I.”

The Drama Queen’s story begins, like the second Jack-in-the-Box’s, with the death of a parental figure – and while Jack Johnson had loved ones he never got around to telling, Frank Darman’s family knew exactly who he was, up to a point…

… but while not knowing what happened to his father or who he really was left a hole in Zack Johnson’s life, knowing exactly who her father was meant that Juliet Darman (of course he named her Juliet) always had someone to blame.

And that leads us to Francesca, who – in contrast to Jerome – has no desire to get out of the life, and no ability to even imagine what life outside of it would look like. She too, represents the dark side of “anyone can be a hero” – a hero needs a villain, and if you need to be a hero, does that mean that someone else needs to be a villain?

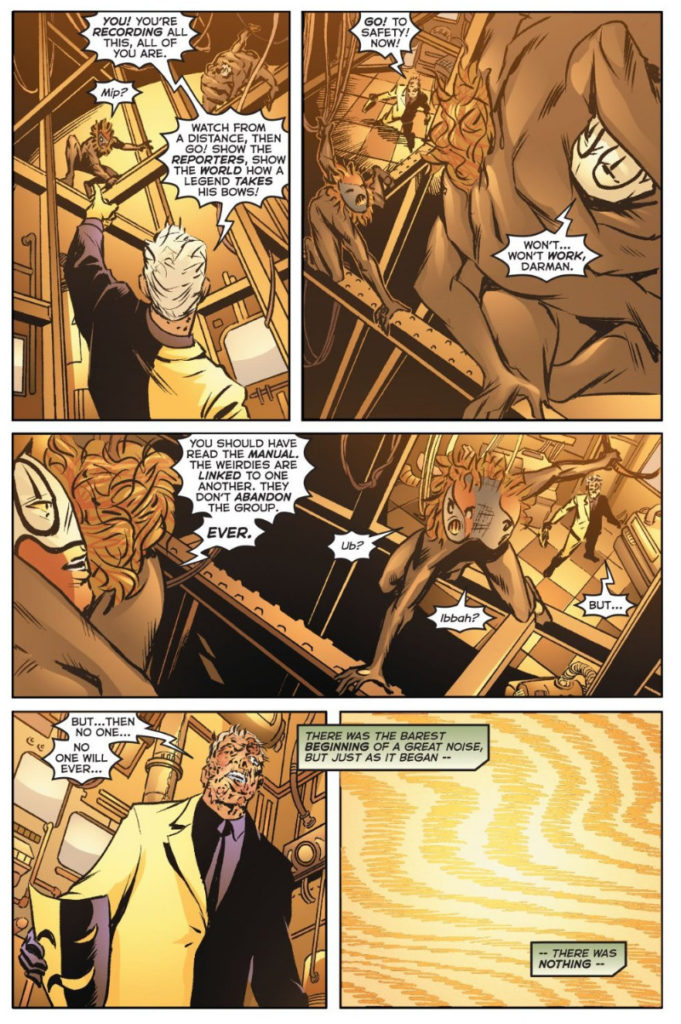

Franchesca, as the Drama Queen, resurrects the “Weirdies” as part of a series of attempts on the life of Jack-in-the-Box, not having fully pieced together the notion of “hey, maybe he’s not actually literally the same hero that killed my great-grandfather” – or just not really caring either way. And that leads to the confrontation at the site of Jack-in-the-Box’s death – because it was the site of the death of Mister Drama, as well.

Through the ability of the “Weirdies” – and no, I’ll never stop putting quotes around that word – to replay their own collective memories, the truth of what happened to Jack-in-the-Box and Mister Drama is revealed. The villain that day wasn’t the Underlord (so, er, maybe that means he shouldn’t be in jail?) but a rapidly dying Mister Drama, determined to find immortality by having a dramatic final confrontation with his arch-nemesis.

But of course, there’s many kinds of drama…

… there’s dramatic irony as well.

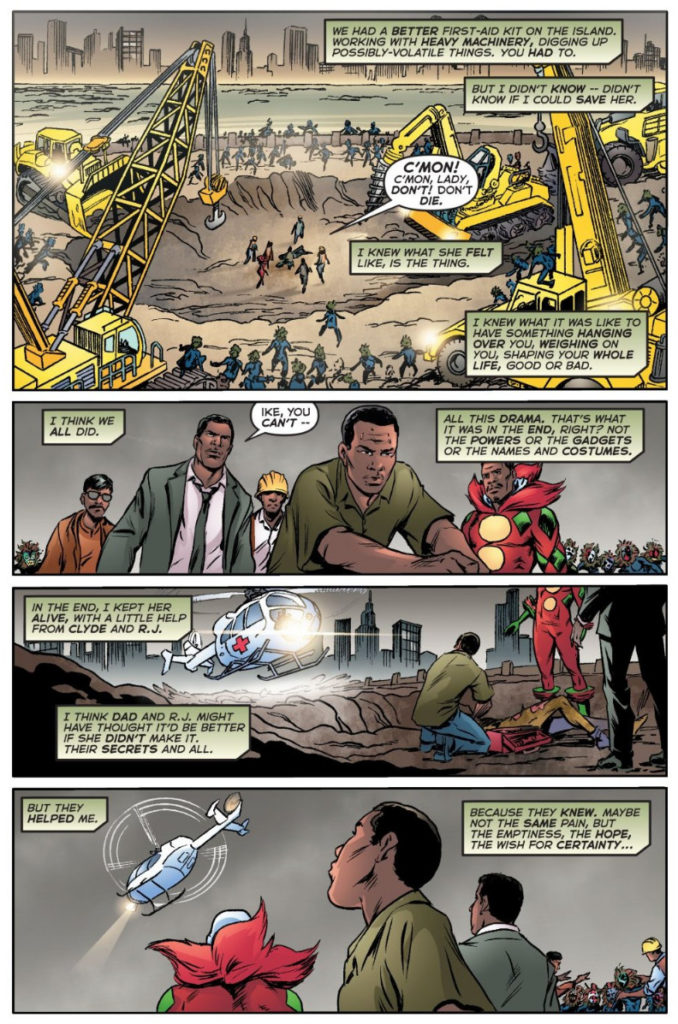

The truth finally revealed is as destructive to Francesca as it was empowering to Zachary – Zachary learned that his father, and his family, was so much more, and the self-proclaimed Drama Queen learns hers is so much less. She pulls a melodramatic move – right out of Shakespeare – and attempts suicide…

… and Jerome fully comes into himself, refusing to let her die – not because he’s a superhero, but because he’s a doctor, and sometimes that means the same thing, that you can’t let someone leave this world via your inaction.

Jerome, in the end, comes clean to his family, who are all quite accepting, and he finds himself wondering if the Drama Queen could be helped in ways that are a little more prudent than a sock in the jaw and a trip to the slammer. Having positioned himself outside the paradigm, he’s now allowed to question it.

Anyone can be a hero, and sometimes being the hero means being a different kind of hero: your kind. And if Jerome decides to take a pass on being Jack-in-the-Box – a decision all but made for him, in many ways – there are plenty of others ready to take up the cause. When you have enough characters of a particular intersection of identity in entertainment – when you have an entire heroic legacy centered around black manhood – then it’s okay for one of them to refuse the call for their own sake. When you have enough heroes, they don’t all have to be heroes.

Next week: the long-awaited secret origin of the Broken Man, who is more than he – or they – appear to be…

Leave a Reply