In one of life’s weird synchronicities, I got around to writing this a day or two before I went to see Aquaman…

… so I’m in just the right mood for adventures with oxygen bubbles on sea turtles. Especially ones as lavishly drawn as Jesus Merino, who drew the extremely horny comic about Starfighter but here is much more restrained, limiting all thirst to shirtless jaguar men with heat vision (which I’m sure is appreciated more than he knows.)

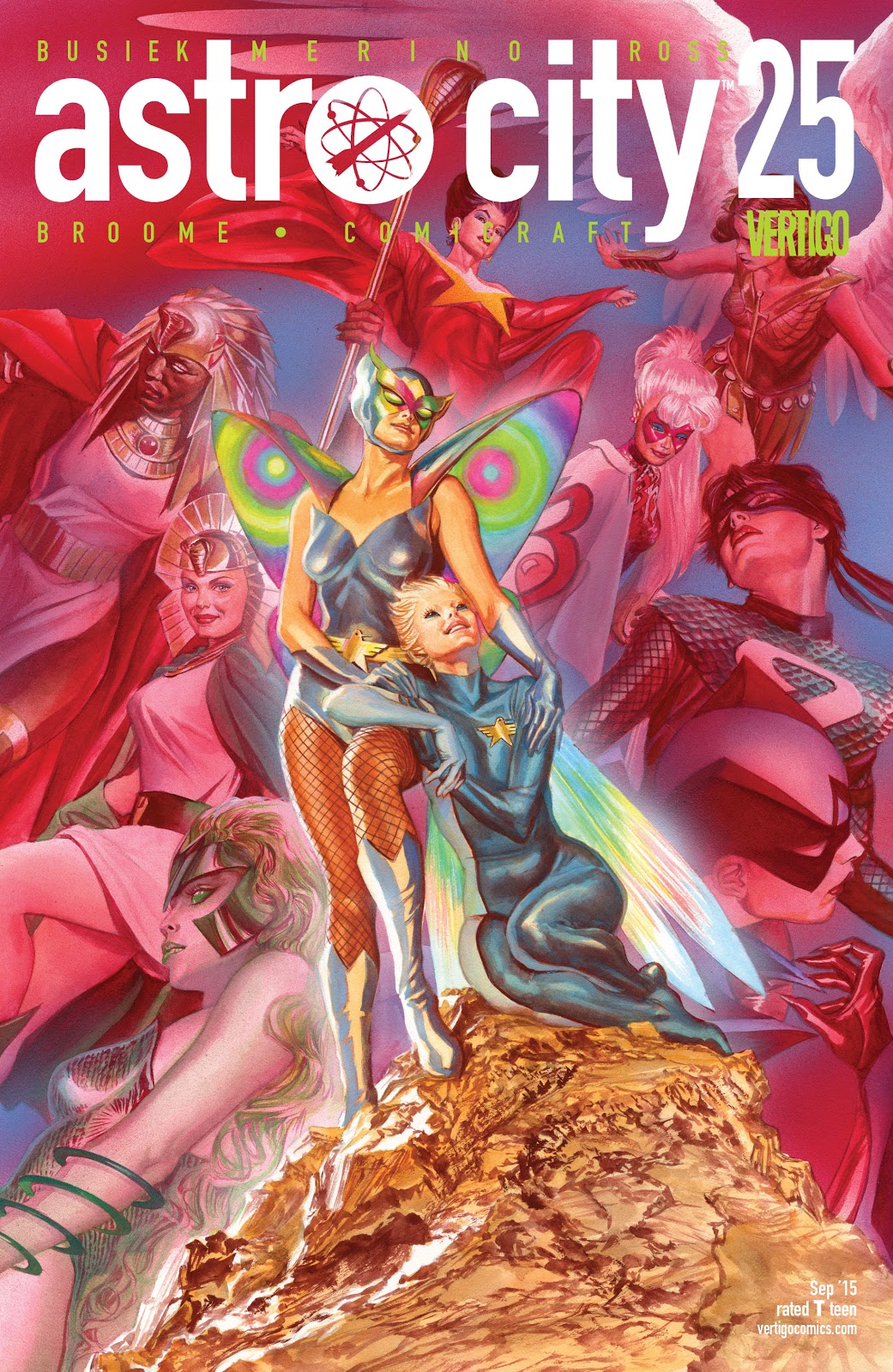

“Lucky Girl” is about a mother-daughter superheroic relationship, which is one of the most iconic notions in superhero comics – from its purest, most iconic form in Hippolyta and Diana in Wonder Woman, to its pre- and post-Crisis incarnations with Black Canary, to even its deconstruction in Watchmen with Laurie and her mother Sally. It doesn’t necessarily feel iconic to many because sadly, female superheroes still have a ways to go.

This story is about Hummingbird – specifically the second Hummingbird, Manda, who has that all-too-common quirk of getting real superpowers based on what her parent accomplished with technology and martial arts. I’d say “genetics doesn’t work that way” but to be quite honest, genetics and superheroics have been on a break for a while now and they’re not getting back together any time soon. I don’t know why this bugs me but the notion that getting angry means you can wave good-bye to conversation of mass; it just does.

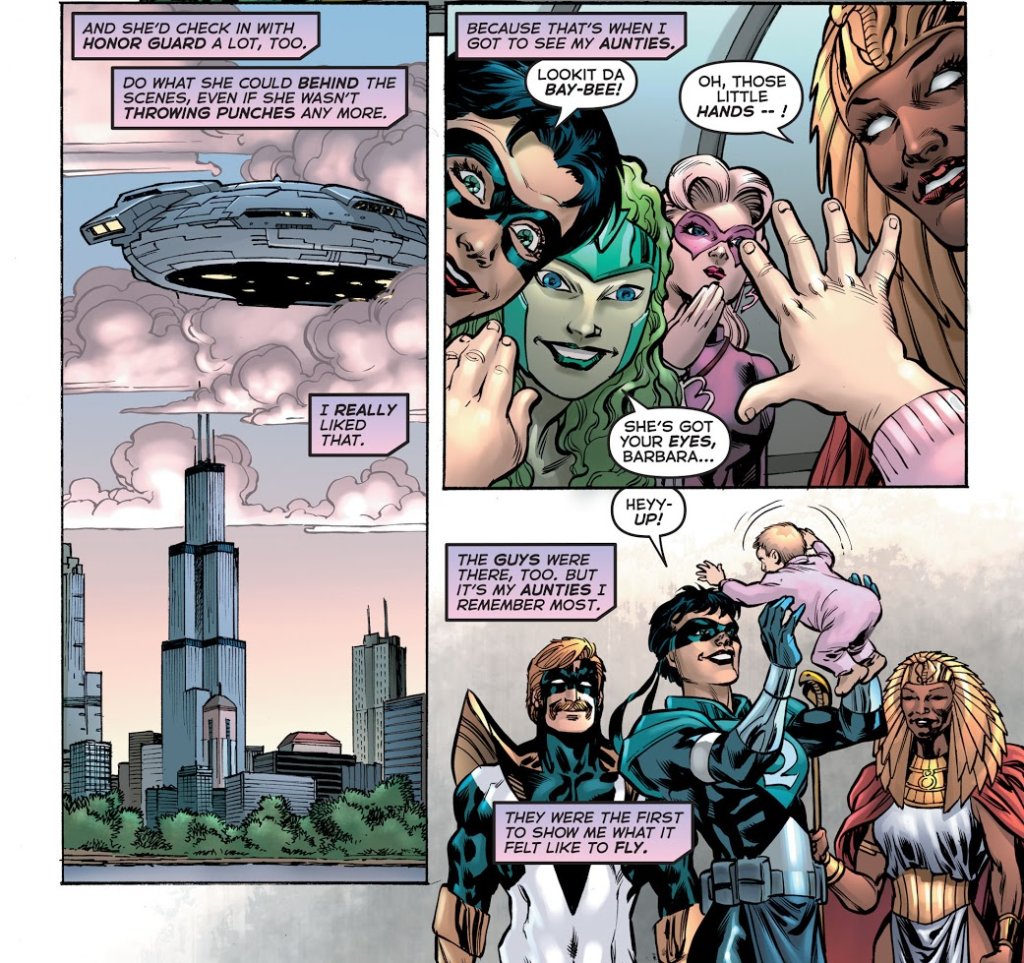

Manda tells the story of who she is and how she came to be – how her mother and father had a love that crossed worlds, and that he had to leave her behind, and that his gods had blessed her birth. Then Manda enters the picture and recalls life growing up where a bunch of superheroines are your honorary aunt, from the very human Quarrel to the goddess Cleopatra to the Pinocchio-like Beautie (an actual living doll.) This is actually a very sweet story, in part because of how it focuses on generational bonds between women – which is, again, an iconic story.

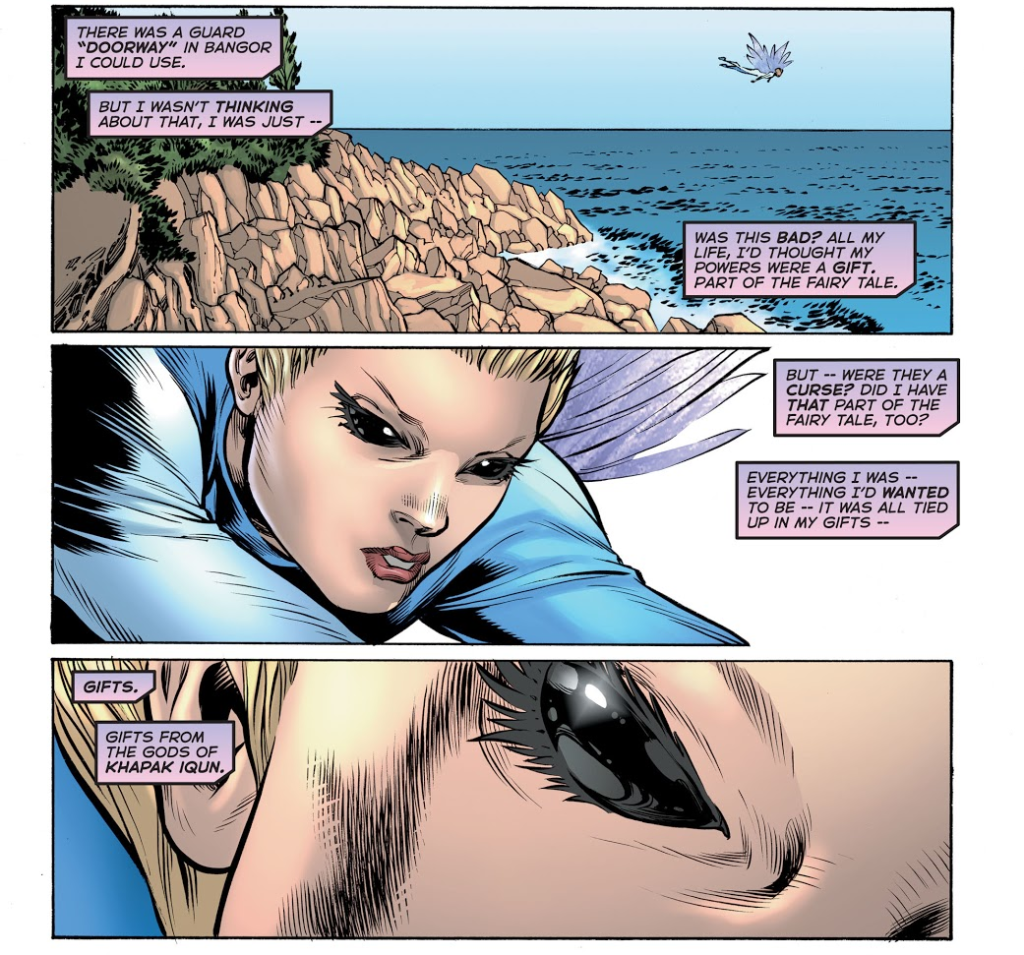

But there’s a wrinkle, and the wrinkle is this: the superpowers that Hummingbird is manifesting are magical in nature, and they have a dark side – they’re turning her into a bird. It’s all a plot by her father’s demi-god arch-nemesis to lure them back to the parallel universe that he and his people fled to, a curse slipped in with blessings.

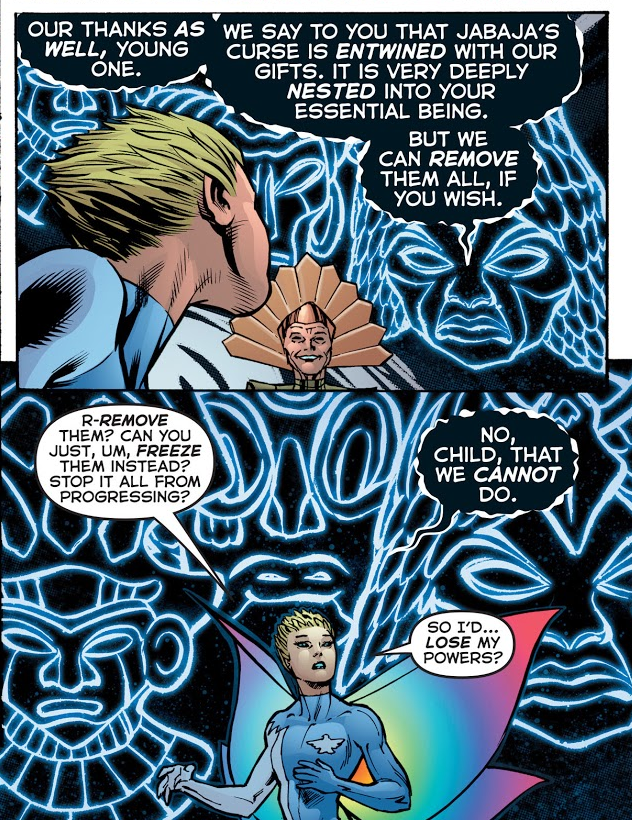

Hummingbird defeats the god, saves the day, and is informed that the curse is part of her blessings – that in effect, her powers are a form of chronic illness, and that removing the curse means she loses all her powers, as well. I’m… not sure I’m entirely on board with this.

I do think that complaints about problems with, say, the Mutant Metaphor are overplayed – I think it’s quite easy to explain that people treating non-mutant superhumans differently than mutants can be a pretty solid illustration of the irrationalities of bigotry, since people have no issue treating cis people differently than trans people of the same gender. But those problems do need to be managed if you think about them – for example, mutants are probably more effective as a metaphor for how marginalized people can be oppressed along one axis but privileged along another, because oppression doesn’t come with neat superpowers. “The ability to do what few others can,” when wedded without due care to the notion of oppression, can play into notion that people who are marginalized actually have unfair advantages – if you take comics too seriously, which a lot of people do.

Something like a chronic condition – superpowers that come with a downside – also need to be handled with a fair bit of care, because most conditions don’t come with the upside of being able to fly and shatter glass with a loud yell. I have a minor spine injury from a car accident as a child and it didn’t give me the ability to talk to fish (or at least, if it has, they’re just being jerks and ignoring me.) There’s examples of superheroes whose superpowers are standins for disability or a chronic condition, like Daredevil, but Daredevil has in turn come in for lots of criticism over the years as to how it handles disability issues.

This is, if nothing else, part of the genre; powers with tradeoffs are – again – part of the X-Men approach to superpowers, especially for mutants who are stuck in their alternate forms. So Astro City didn’t invent the notion and it’s entirely possible I’m reading too much into it – at no point is the comparison to a chronic condition made, and while my interpretation may be valid, it’s possible it’s more from me than from the text itself.

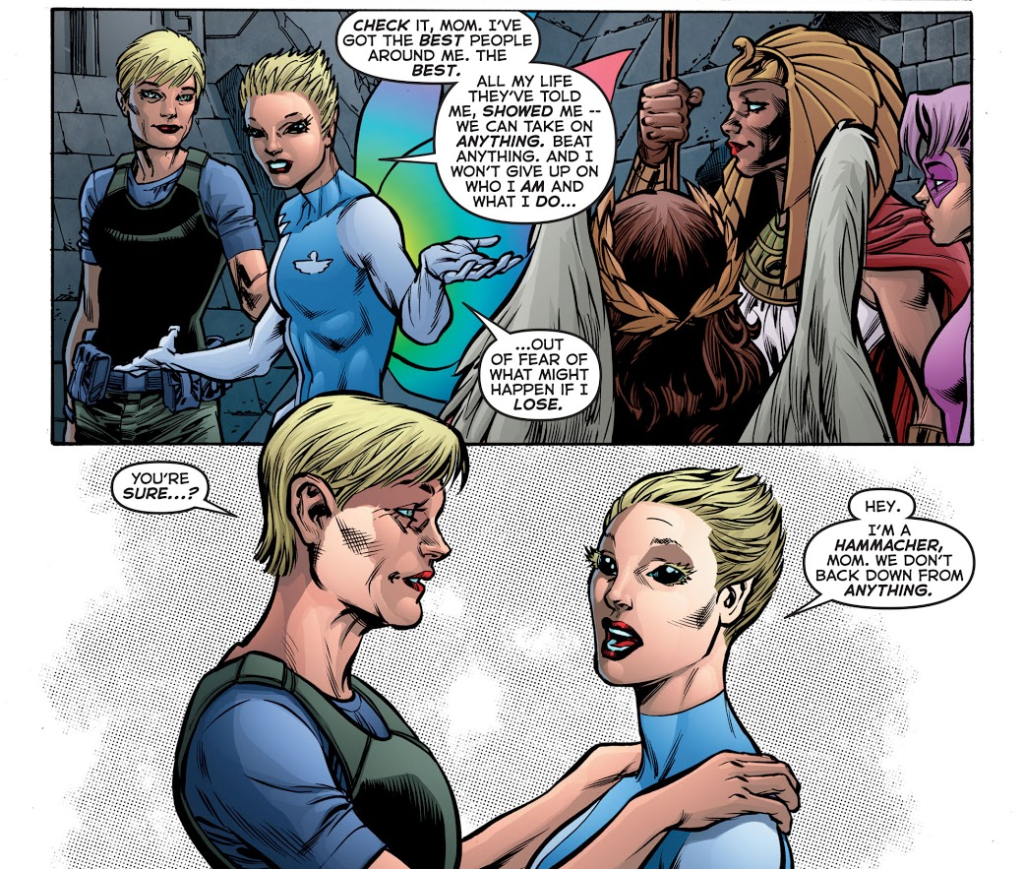

If it is intentional, then one upside of this interpretation is that there’s no miracle cure; Hummingbird has to either take the entirety of her version of superhumanity, or leave it, and she chooses to keep it. No one with such a condition gets the option of its removal, but the explicit rejection still works – because to Hummingbird, this is an essential part of her life, no matter how it’s going to end.

Too many times, a story treats a part of one’s identity to be cured, bringing up uncomfortable comparisons to everything from forcing left-handed people to mess up their brains rather than having them write with their left hands, to conversion therapy and all its attendant horrors. If the metaphor has a flaw, at least it’s not this one.

This was issue #25, which is typically the anniversary issue these days – but the anniversary has been postponed, as issue #26 marks 20 years of Astro City exactly. What’s changed? What hasn’t? Find out, next time.

Leave a Reply