We live in the age of the pop culture revival, and the arrival of the eternal film and movie franchises, all born or borrowing from the model of superhero comics storytelling. Astro City, one of the most storied and beloved superhero comics of all time, went through a revival of its own in 2013, and that it came back as strong as ever was a miracle in and of itself. Over the course of a year, Charlotte Finn will be examining this miracle – all 52 issues – as she spends A Year in the Big City.

Analogues aren’t unique to superheroes, but I can’t name another genre that makes more frequent use of them.

The reason so many analogues abound in the superheroic genre is because the ideas behind them are both visually potent and tied up in copyright. Everyone wants to draw or write their favorite superhero, but the chances of you actually getting to draw or write that superhero for money are vanishingly small. As Geoff Johns once remarked, there are fewer comics writers in America with that vocation as primary income than there are players in the NBA. Those are tall odds to vault over for a mere mortal, and thanks to corporate pressure to extend copyright indefinitely, the likelihood of these characters entering the public domain any time soon are even smaller.

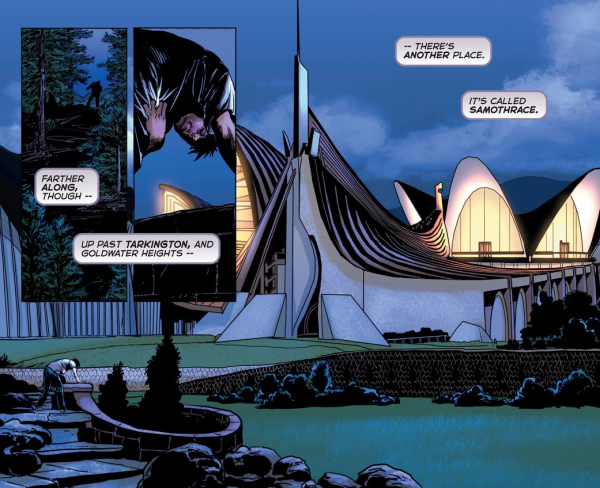

So, we get analogues. Megamind’s not actually starring Superman, Lois Lane, Lex Luthor and Jimmy Olsen, but: c’mon. The Squadron Supreme, despite existing solely so that there can be unofficial DC-Marvel crossovers, are all technically Original Characters (Do Not Steal) but: c’mon. The official word from Astro City’s creative team is that these aren’t analogues, and I get it, but the second one of Winged Victory’s outreach centers is named after a Greek island…

… c’mon.

There is, to be clear, not one single problem with using an analogue, especially of characters as old as DC’s Golden Age characters. There was, not too long ago, two concurrently running Sherlock Holmes TV series and a movie series as well, and this is made possible by Sherlock Holmes being in the public domain – a place where, by now, The World’s Other Greatest Detective ought to be. Characters like these should belong to everyone, because they’re so soaked into the cultural firmament that everyone has an option on them and a direction they want to take them, and art is built on the cultural firmament. It’s not the same thing as actually having a robust public domain, but it’s a nice enough workaround.

This story, therefore, is about Winged Victory, as well as a character she is meant to evoke, and what makes them similar (and what makes them different.) Of the three characters who most map to DC’s Trinity, Winged Victory’s been the most underexplored – Samaritan was in the very first Astro City comic and his origin was revealed in the sixth, and the Confessor’s origin played out before us without us knowing it during the seminal Confessions storyline. Sadly, this fits the mold; six issues for the Batman-alike, two for the Superman expy, and “we’ll get around to it” for the Wonder Woman supposed-to-be.

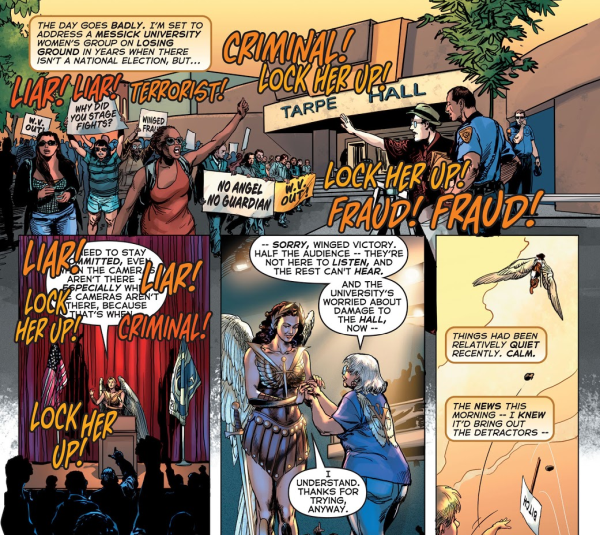

But maybe that’s unfair, because this storyline is worth the wait. It begins with a boy being admitted to one of the outreach centers, his health in dire straits, and this happening concurrently with an attack on Winged Victory politically, her most frequent villains accusing her of paying them off to make her look good.

Everything goes south rapidly, because accusations like this – due to everything from internalized biases to bigotries worn on one’s sleeve – stick to the marginalized more than they stick to anyone else. Seeing “lock her up” chanted about a politically active woman certainly feels different now than it did in 2014, and the fact that I still hear that chant, and have for the past three years, is proof that in the words of Zoe Quinn, August never ends.

(Special credit to the lettering team – John G Roshell and Jimmy Betancourt of Comicraft – for the depiction of what it means to be audibly drowned out by big ugly chants overriding your reasoned speech.)

Winged Victory’s supporting cast all have different ideas on how to handle it, all of them drawn with simple visual designs and broad strokes in dialogue that they instantly feel familiar, from the loud and brash Meg to the more contemplative and unassuming Delphi. At one point, Winged Victory relates her secret origin, and here is where the similarities to – and differences with – Wonder Woman are delineated.

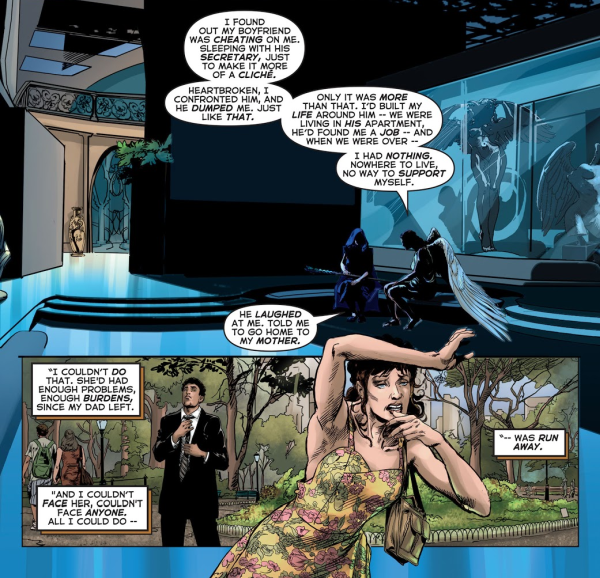

Like Wonder Woman, Winged Victory evokes Greek mythology, though it’s both more centered (right there in the name) and less centered (a surprising lack of gods.) Like Wonder Woman, she’s meant to be not just a feminine hero, but a feminist hero. But there’s no Paradise Island for her – she comes from very mortal circumstances, lost and adrift when she woke up one morning to find out that she’d built her entire life around a man she couldn’t trust any more, any kind of independent support structure cut off and gone.

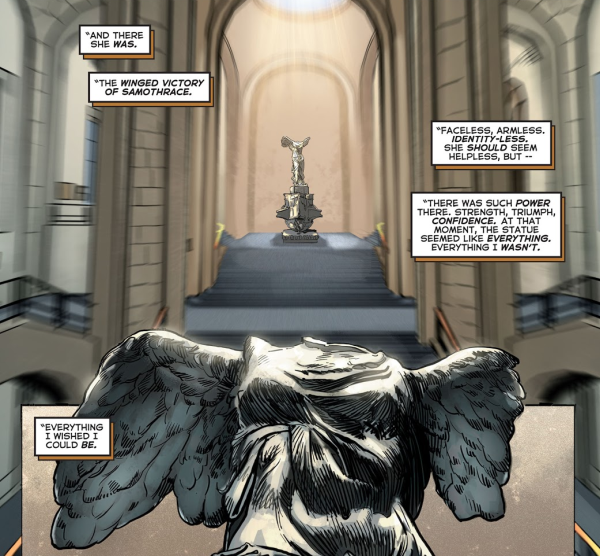

She finds the Winged Victory of Samothrace, an icon that – robbed of its identity – can be just like a superhero, a ready-made icon you can just pour yourself into.

For her, Paradise Island is a destination, not an origin point, which changes up the story fundamentally while staying true to its core. Rather than an army of similarly powerful Amazons, there’s the Council of Nike, a psychic collective of women the world over that empowers her as their champion. This council’s faith in her has begun to falter, sapping her abilities on top of everything else, because their consensus on her is hampered by recent controversy and they weigh whether she can be a vessel for their work any longer.

Having Winged Victory’s powers come from, essentially, Politics Writ Large – the act of forming consensus, organizing and building power – is a great idea, because it ensures that the feminism of Winged Victory is the feminism of Right Now. Feminism, like every other social movement, is a movement; it gains and loses momentum, changes direction and isn’t the same thing now that it was even a decade ago. It means that instead of feeling you have to reboot the character for a new generation – sometimes three or four times in a generation, not that I’m counting or anything – you can just have the concerns and aims of the Council of Nike change organically over time.

Of course, the downside of a movement is that it can leave people behind, and Winged Victory is beginning to worry that’ll happen to her, and all of her work will be undone over a lie. And to complicate things, an old face returns…

… but he’s not the same old face – or rather, he is, but he’s an old face in a new mask. Or an old mask, because it’s the same mask that – listen, it’ll make sense next week once we are formally (re)introduced to the Confessor. See you then!

Leave a Reply