The “You Probably Saw It” List

Why? Come on now.

Smarter (and less white) critics than I have pointed out all there is to point out with Black Panther, so the part that sticks out for me is how it always seems to be one step ahead of the viewer. You come in to the theatre and you’re given what would be paradise for the African American – a world where all the pains of America simply aren’t. Then you ask yourself whether this paradise can really be just if it’s a gated paradise, because America is still out there and all its sins still extant – and then it turns out that both the villain and one of the heroes agrees with you.

The Marvel Villain Problem has been solved – possibly temporarily, but still solved – in films such as Spider-Man: Homecoming and Thor: Ragnarok, where the villain has a legitimate grievance but has taken it too far, but examination of that legitimate grievance leads to a character arc for the hero or heroes. It’s done well in those movies, but best in Black Panther, whose villain is the best Marvel villain and who has spurred a legitimately fascinating discussion on black liberation theory translated into praxis – all this from a movie about a man in a metal cat suit, proving that things are only ridiculous right up until we believe in them.

Black Panther is neck-and-neck with Captain America: The Winter Soldier for me in terms of Best Marvel Movie. It’s an outstanding achievement on every level and one of the year’s best – and this year was an exceptional year for movies.

Why? Probably the least good movie on this list, and not the pop culture watershed that was Avengers (2012,) but still a favorite, for a lot of reasons.

First, everyone who was complaining about how Marvel movies were all explosions and high-fives where no one really got hurt and that all Thanos did was sit on a throne and not do anything sure aren’t saying that after Infinity War, which takes every mode of heroism and breaks it over Thanos’ big purple knee. The pragmatism of Star-Lord doing as Nebula asks and trying to shoot her doesn’t save the day. The “wildcard who’s on his own side but who’ll turn face just long enough to give the heroes a chance” turn that Loki takes doesn’t save the day. The idealism of Cap and the Avengers refusing to kill Vision doesn’t save the day. The pragmatism of them finally killing the Vision doesn’t save the day. Thor’s awesome new hammer that’s been built up to over the course of the movie doesn’t save the day. Sometimes, shit goes wrong, and goes horribly wrong, and suddenly everything tastes like ashes. (Of course, that’s a completely unrelatable notion in 2018…)

Of course, there’s an out, hinted at (okay, stated flat out) by Doctor Strange, who gets the most improved character award by a mile. His own movie is okay – improved greatly by the unconventional ending but it is a trot and a half to get there – but here he is full-on Doctor Strange, the 800 pound heavyweight of the Marvel Universe, the man who won’t hesitate for a minute to carry out a plan even if it means he’ll be horribly tortured or killed, the one who will have a sorcerer’s duel in space with a mad god. I like Doctor Strange a lot, and it’s awesome to finally see the character get his due.

And ultimately, what makes it work is that while it subverts your expectations of a Marvel movie – all your favorite characters are in hell – it still is all your favorites, an entire movie that’s a George Perez cover of forty superheroes smacking the shit out of people. I’m not about to act like I don’t think that’s cool. Bucky and Rocket share ten seconds, but they’re exactly the ten seconds you want. A long-running joke with a racoon who likes to rip cybernetic parts out of people finally reaches fruition when Thor gets a new eye – a nice touch that shows how Thor is being built back up by his new friends. And while Thor isn’t quite the same yuckster he was in Ragnarok, I’ll go there and say that the Russos did more to keep him consistent with Ragnarok that Waititi did to keep Thor consistent with the previous two Thor movies.

I wouldn’t want every superhero movie to be a massive all-the-marbles crossover which ends on the most downer note in history (just like I wouldn’t want every superhero comic to be, and please, God, Marvel Comics, stop.) But I’m glad this one is, if for no other reason than because it’ll make future moments of triumph sweeter for the denial.

Why? Infinity War shouldn’t work, but it does; however, Spider-Verse really shouldn’t work, and it works great.

Narration? The bane of most movies, yet Spider-Verse has constant narration, often interspersed with text narration on screen, and it all works, ensuring that nothing ever drags (because while showing is better than telling, sometimes telling is faster than showing.) Animating foreground figures at a different frame rate than the backgrounds? Takes two seconds to get used to and makes foreground figures pop beautifully. Seven origin stories, including one that’s the whole movie, and the character who’s having the movie-length origin doesn’t get his costume until act 3? It turns out people aren’t bored of feature-length superhero origins after all – they’re just bored of boring ones.

Miles carries this entire movie, being the last Spider-Man standing at the end – concerns that he’d be crowded out in his own movie were unfounded. By the end, he is Spider-Man, in name and deed and reputation. But everyone’s done well – older schlub Peter Parker is walked back from the crushing defeat of Life in General After Thirty-Five, Gwen Stacy has finally excised her fridge moment from public consciousness, and even May Parker is done well by. (Peni Parker, Spider-Man Noir and Spider-Ham are largely superfluous to the plot, but they’re workable second bananas and this is a cartoon, so it’s okay to have those.)

It’s an absolute triumph visually as well – you’ve seen the trailer, but the trailer doesn’t get into even half of the visual tricks it pulls out. And the visual tricks do more than look great – they underscore the feeling of the movie, a world where the first assumption is that superheroes exist and are awesome. This means that stuff that would be nitpicked in live-action gets a pass. Is a teenage boy – even a biracial black teenage boy – really the best protector for New York? Is Miles pro-cop, because he loves his Dad, and is that bad? Is it a violation of Kingpin’s civil rights to web him 50 feet in the air between buildings after he’s tried to collapse the multiverse? All questions that are answered with who cares, it’s a cartoon. Perhaps the best response to the questions posed by Civil War is to be so dazzling and amazing that no one thinks to ask them.

Why? Finally, a non-superhero film! Technically.

A lot of hay has been made about how Tom Cruise is trying to be the modern day Buster Keaton (he isn’t, you’re thinking of Keanu Reeves.) And it’s true, there is something about seeing an actual human being nearly get turned into strawberry jam leaping out of an airplane that thrills the mind, because good as computers are, they aren’t that good yet.

But if I want to see a damn fool almost die, I have YouTube. What makes this movie more than an afternoon typing “parkour fails” into my phone is that, while it is not the best Mission Impossible movie, it is the most Mission Impossible movie, the one that completes an arc that was less planned and more emergent, starting with the surprisingly underrated Mission Impossible 3 and continuing through the new series formula laid down in Ghost Protocol and refined in Rogue Nation.

The series has emerged out the other end as one of the most fruitful branches springing from the trunk of the spy genre that is James Bond – not afraid to have fun gizmos and fun gadgets, but also not afraid to grapple with the seedy realpolitik of tradecraft, and most unlike Bond, not afraid to lay down some firm continuity in this age of Netflix where catching up on a popular movie series is easy and cheap. (Yes, Bond has tried to do this. Key word being ‘tried.’)

Why? Statistically, you saw this, since it made buckets of cash. (Hopefully you didn’t see this in a movie where someone insisted on talking through a highly tense climax, like I did. Even if you don’t like the movie, don’t ruin it for someone else.)

I know that Hereditary is the lock for “better” horror movie, but Hereditary lost me after a gratuitous, lengthy close-up of a child’s ant-covered severed head, which took me from “oh God” to “oh, fuck you” in the space of ten seconds. A Quiet Place is, to me, a more pure example of the parent-horror genre, where they straight up kill a kid because that’s a taboo that you can still break and have it be shocking. Said child dies in the beginning and their loss is felt all throughout the movie, so whatever gratuitous shock is gone and the movie has to rely on how it’s affected everyone around them.

And that all of how this has affected them is clear, and told with very little sound, making a movie where something as simple as a nail is as deadly as Chekov’s Gun. And best of all, it thematically swerves you by taking a deaf girl – who would almost certainly be considered a liability in the traditionally codified (i.e. sexist, racist, ableist, homophobic, you-know it) post-zombie rules of survival – and having what makes her different be the key to defeating the monsters in the end. It lets you let out that breath you’ve been holding for the movie’s taut, not-a-moment-wasted runtime. What a great film.

The “You Probably Heard of It” List

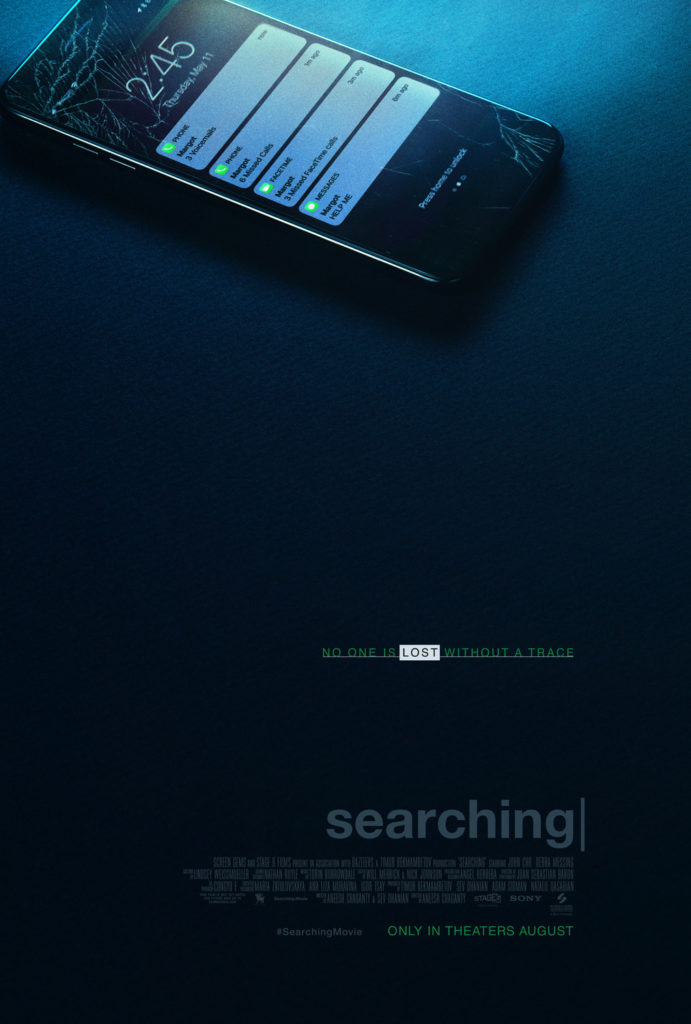

Why? It opens with a gag about the Windows XP desktop, and it lands.

Movies are based around visual language, and what we understand visually changes due to time and culture and other constraints. The visual beat of shifting a gear stick is only understandable after the widespread adoption of the car; you can only have a gag about someone’s reaction to a telephone conversation you only hear one side of, if you’ve heard one in your life. The entirety of the found footage movie is based on the popularity of the handheld, commercially available film camera growing to the point that many people’s first movies were ones staring themselves and shot by their parents.

Searching is a movie about the visual language of using a personal computer – something I’m incredibly familiar with, but now the rest of the world is familiar with enough that a movie can actually have widespread appeal instead of being a novelty. It weaves in character beats, backstory, and hints about the lead character’s emotional state. The computer is now fully the extension of ourselves – how it’s used can show how we feel, up to and including the growing “wait a minute” moment of uncertainty as a plot twist is revealed.

And there are so many good plot twists in Searching – above all else, it’s a damn fine thriller and has everything you want in a movie, from humor to heartbreak, all anchored by John Cho, who deserves consideration for Best Actor based on how well this movie is anchored by his performance. This might give birth to a new style of filmmaking the way Blair Witch Project popularized the found footage movie – and Searching is a lot easier to watch on the big screen.

Why? The bear (that fucking bear) gets all the hype, but it’s because that’s the moment where all the accumulated unsettling nature of the Shimmer veers into all-out horror of the “there’s a monster in the room” variety. The rest of the time, the horror of Annihilation is more low-key – but no less disturbing.

Usually horror movies scare us with the concept of death, of us ceasing to be because of something else. But sometimes they scare us with the concept of not dying – of a fate worse than death. Of, essentially, having too much life. Of, for example, having a part of you trapped inside of the thing that killed you, so that when it roars, your screams for help are heard. Or of grass growing out of your scars as you surrender to inevitable fate and are turned into a plant – but a plant that is, in some ways, still you. Of having your insides cut open and they’re alive and moving around, and beautiful fungal blooms sprout from your corpse and fill a wall. Annihilation is a movie about a section of the world where there’s too much life.

It’s probably the best Lovecraftian movie (the premise is basically The Color Out of Space.) Many people disparage the ending, where the cosmic horror is defeated fairly easily, but personally my read of the ending is that – thanks to a disappearing facial wound, and a cut where the final entity of the Shimmer goes from behind the heroine to in front of her – the horror wasn’t defeated, but that the Lena that went in wasn’t the Lena that came out. But then again, given how much of Annihilation is a metaphor for trauma and how it changes people, Lena was never going to be the same coming out regardless, even if it’s her at the end. That’s why it’s great.

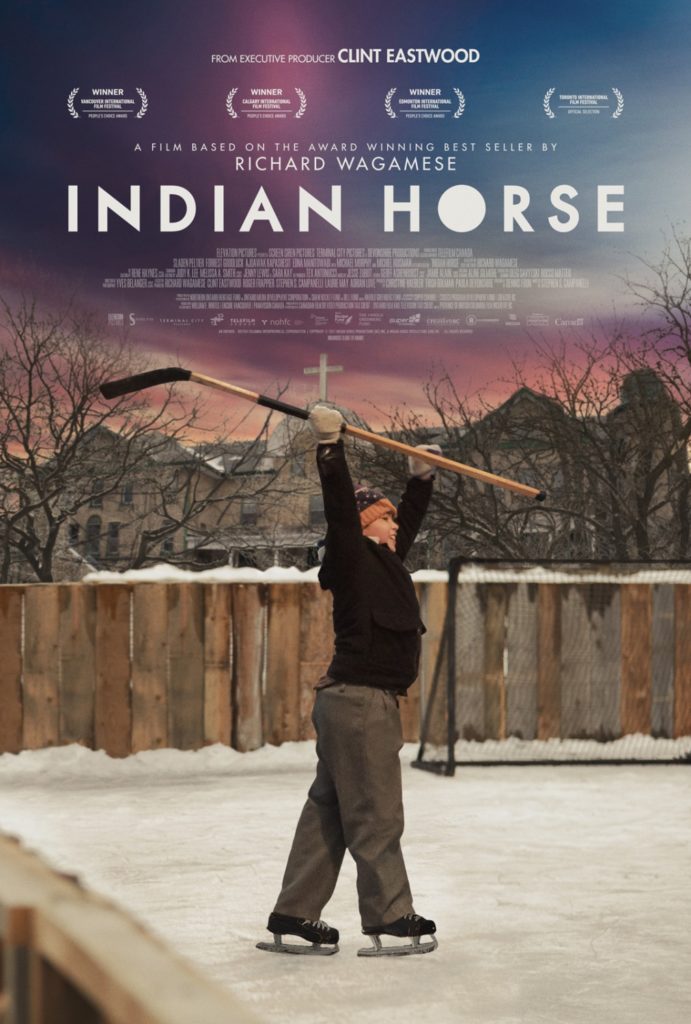

Why? You could make a dozen movies – a hundred – about the legacy of Canada’s residential school system, and it wouldn’t be enough. Calling it our great national shame seems to incredibly diminish it, because it implies that it’s an anomaly in how the people of the First Nations have been treated in Canada, rather than just one link in a centuries-long chain of sin.

Usually in sports movies, even based-on-a-true-story ones – because there’s fifty billion true stories throughout history, and so the question is, whose story gets told – there is a structure. The marginalized character is good at sports! But he faces discrimination! But – through the power of playing really good, he wins through!

That does not happen in Indian Horse. Saul Indian Horse does not triumph, changing sports forever; he walks away from a sport where he’s loathed. He falls on horrible times and fines his way out of them with the help of family and friends. He never finds redress for the traumas inflicted upon him as a child. But he finds a way to go on, nonetheless.

Anyone can sympathize with a hero – and in fact, “one of the good ones” is one of the ways systems of oppression maintain their grip, by pointing to the one that slipped through its fingers as proof that the fingers aren’t there. What Indian Horse asks us to do is to feel empathy for those who didn’t beat the odds, and asks us what role that settler Canada – myself included – had in stacking those odds to begin with.

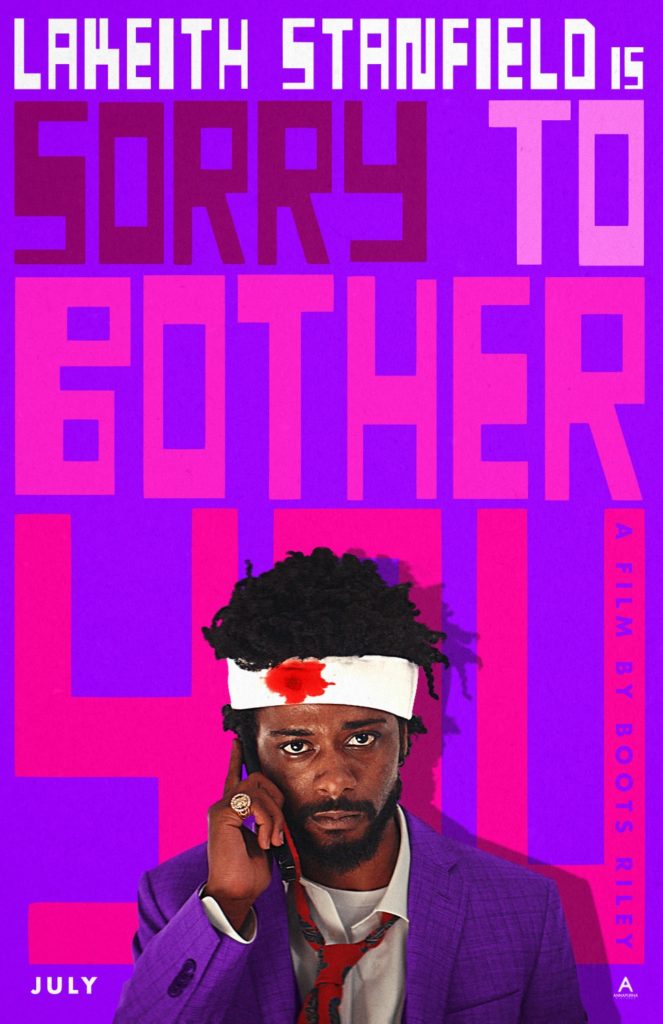

Why? This movie convinced me, single-handedly, that satire is not dead. It’s tough for satire to catch up with reality, so Sorry to Bother You instead creates a one-step-left alternate universe where its surrealism is reality, and reflects back to us just how bananas life in 2018 really is. This movie is weird, and gloriously so – but it is never gratuitously so. It’s the illuminating power of surrealism in the same vein as dril or da share z0ne, in movie form. What I tweeted after seeing it holds up: I simultaneously have no idea what I saw, and I understood it perfectly.

The way this movie is shot, with rooms next to each other that should not be next to each other, where the barrier between Cassius and the people he’s calling disappears as soon as they’re connected by technology, where slave labor is sold two floors up from where encyclopedias are sold – it all gives an impression of compressed space, a world that’s jumbled. And it’s not the only jumbled thing in the movie, as background plotlines inform us of new subplots via Michel Gondrey style cartoons and a shot of a slave labor camp in the style of MTV Cribs. The overriding feeling of the movie is “well, that’s a new thing I have to know about, I guess” – and that’s the single most 2018 sentiment I can think of.

It has the funniest line of any movie I’ve seen this year and I can’t explain why the words “same struggle – same fight” reduce me to fits of laughter, both for how sincerely the sentiment is expressed, and the completely logical series of events that lead to it. And most of all, it is sincere in its beliefs; sincere about the desperation of being poor, black and desperate, sincere about how that excuses some things but not everything and not forever, and sincere about how in the end, we have each other, even if some of us are [REDACTED]. My favorite 2018 film.

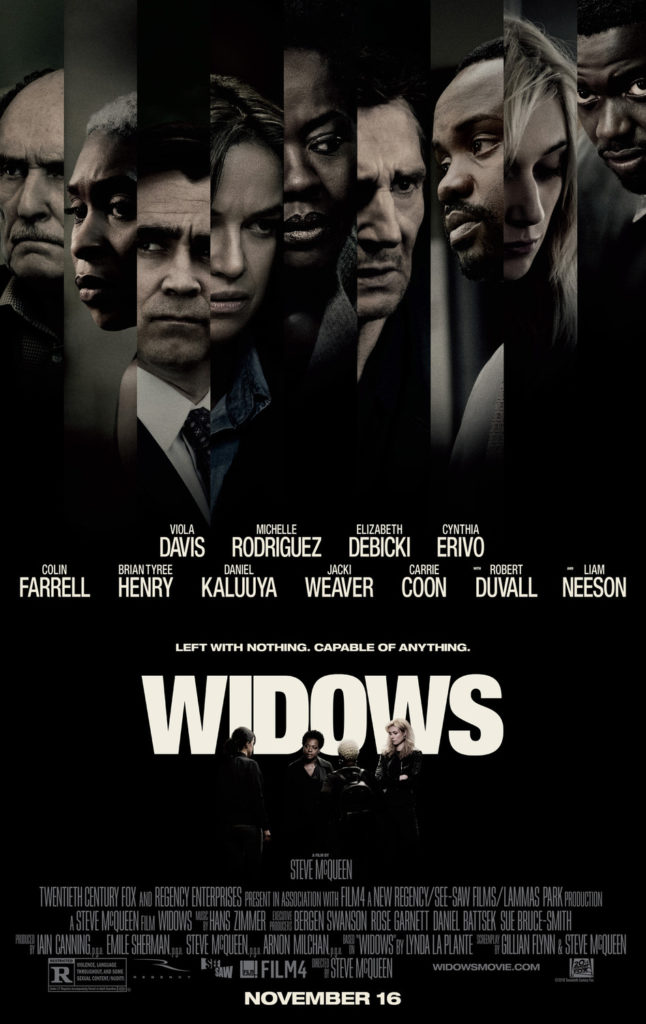

Why? The best compliment I can pay this movie is that every hit it dishes out, hits as hard as the movie wants you to feel. Every twist is as devastating as it ought to be; every acting turn by its leads is as potent, forceful, stoic or understated as is needed; every shot knows its function and is unafraid to be showy when needed (such as the switch from one side of the street to the other) and understated when it’s best.

There are comparisons linking this to Ocean’s 8 but this is as different from Ocean’s 8 as that movie is from, say, Heat; this is a heist movie, but not a charming feel-good heist movie in the style of the Ocean’s films or Leverage. This isn’t a band of super-competent master criminals, but desperate women who are on the hook for something they didn’t do – and usually in crime stories that means they were framed, but this is a women-focused crime story so all that means is that their husbands did the sin and they’re stuck with the penance.

Beyond that, this is a story about local politics and how sleazy and corrupt politics in a place like Chicago can be, as illuminated in one sequence where the length of a phone conversation and the crossing of a street is all it takes to separate the poor from the rich. The interplay of politicians vying for power and influence almost threatens to derail the main plot of the heist – but instead contributes to it, showing that no story is entirely in a vacuum and these details matter.

The “You Probably Haven’t Heard of It” List

Why? Gang, being trans is tough. Even the one-foot-in-the-closet half-ass bullshit way I live my life is pretty tough, and much, much harder if you’re out.

There’s value in stories that allow me to ignore this, and stories like this that pointedly do not ignore this can often feel like misery porn. But sometimes you just have to admit that the world can be shitty to trans people, and that there’s value is feeling that you’re not alone, and that others are also going through their own fucked up, messy queer life. And that leads to Daniela Vega, the star of A Fantastic Woman and who is an absolute tour de force – with a lesser actress (or, God help us, a cis one) this movie would feel exploitative instead of authentic.

Her character, Marina, gets the world dumped on her, and just has to keep going, jumping through gatekeeping hoops and abusive men and women and wanting her dog back; but she also sings as a nightclub singer, tries to make it through the day as a waitress, and emerges from her period of mourning having made it all a part of her, and moved on. I want to see much, much more of Daniela Vega, who deserves a long career after this.

Why? Despite these both being heist movies, American Animals is very different from Widows – or indeed, from most any other heist movie you could name. Shot in an unusual documentary style – with the real people involved in the heist interviewed, and at times inserted, into the film itself and its dramatized take on the events of the real-life heist.

And it is a real-life heist, with the brief fantasy of ultra-slick thieves working in perfect unison rapidly going out the window as everything from the heist starts at messy and rapidly turns to ugly. I don’t think I’ll soon forget the sequence with the crying, traumatized librarian and the thief who alternates between screaming in incoherent rage and apologizing to her, which is what happens in an actual crime – people get hurt, people wind up traumatized, and no one is thinking straight.

Everything about the movie subverts our expectations of the heist, down to there possibly not even really being any point to it all – and despite making off with some of the rare books they were after, there’s no moment of satisfaction, no aura of “oh yeah, we did it.” The movie is full of regret, the kind of somberness that comes with a lifetime’s reflection, and it’s one of the most unique and unforgettable movies I’ve seen all year.

Why? I am increasingly convinced that Diablo Cody is doing the heavy lifting in the partnership between Jason Reitman and her, and as proof, there is this movie, which gives Reitman back a lot of the goodwill he lost with Labor Day, and that he immediately spent on The Front Runner which is a big ol’ shrug-emoji of a movie.

Tully is a movie about how being a mother sucks, and how getting older sucks, and that sometimes you can’t be the pile of raw sex and energy you were back in your twenties, even when a living, breathing reminder of that is sharing the house with you as a night nanny. It’s a movie about feeling tired, God, so tired, and so alone, in only the way a mother is – where all your energy pours out of you and nothing comes back in.

A lot of this image is tied around the iconography of the mermaid, forever free in the vastness of the ocean, forever young, forever beautiful – an icon of womanhood as beautiful as it is unreal, as unattainable as trying to sustain yourself on seawater. But even when we move beyond it and accept that that’ll never be us, the image stays with us, and perhaps, helps us in our darkest moments. A funny, warm and human movie, and now Diablo Cody should hopefully get the credit she is due.

Why? This is probably the best year for African-American cinema I can remember, from Black Panther to Sorry to Bother You to BlacKkKlansman to Widows to Beale Street (which I’ve yet to see.) Hopefully not lost in all of this is Blindspotting, which deserves to be more widely talked about. It’s unusual in that it was co-written by the two actors who play its two main stars, a white man named Miles (Rafael Casal) and a black man named Collin (Daveed Diggs) and how their friendship is tested by the injustices of Oakland and the fact that Miles is That Friend.

We’ve all had That Friend, the kind who is maybe a shitty friend, and maybe gets a little too wild, but they’re your friend and you let stuff slide when people are close to you. And despite it all, they’re such a comfort to have around, so steadfastly loyal, that you put it out of your mind – until suddenly, you can’t. Suddenly all you can think about is the fact that yes, he visited you all the time in prison, but you both beat a man to pulp and he gets to walk out while you’re stuck there. That even though they care about you, underneath the span of your friendship is the horrible injustice of society and he just doesn’t get it the way you do.

The friendship between Collin and Miles is the heart of this movie and Diggs and Casal slip so easily into the roles they wrote for themselves – Casal never lets us forget that Miles is a shitty dude and Diggs in turn never acts like he’s here to teach Miles (and through him, White America) a lesson. It is at turns starkly funny, deeply moving and highly uncomfortable. It’s the centerpiece of an outstanding film.

Why? Normally, I’m not a fan of cringe, that kind of sub-subgenre that is about seeing something incredibly awkward and embarrassing play out. The moment I empathize with a character, I feel so bad for them, because I’ve been there. I haven’t fully been there for Kayla Day’s eighth grade experiences – I didn’t have YouTube or active shooting drills, and more crucially, I didn’t have a childhood where my womanhood was acknowledged. Womanhood was a destination I had to find, rather than a pool I was dropped into. But I have had those same feelings.

That sensation that no one’s watching me when I’m at my most sincere, so I have to put on a new fake personality since at least people talk to me when I have it on. That feeling of going to a party and being the dimwit that gave a kid’s present a year too late, now that everyone’s trying not to be a kid. That feeling of not knowing what to say, ever, at any time. That feeling of slowly realizing that something awful almost happened to me. That feeling of the walls coming down a bit when I meet a friend, even if my initial dipshit bonding was over a cartoon we both like. (For me it was Transformers,so I can’t fault Kayla for liking Rick and Morty considering what a fucking embarrassment Transformers fandom is.)

Most of all, that feeling of absurd, out-of-touch teachers and parents who just don’t get it, because right now I don’t get it, and once I get it, I’m no longer the same person, but because I haven’t gotten it yet, I don’t have that perspective. What Eighth Grade did was pluck me out of my life right now and half-showed me, half-reminded me, of the life I both had and didn’t have. Not every movie can do that.

The “Well, I Liked It” List

Why? To be clear, there is about half of Buster Scruggs that I can leave behind; there’s no excuse for Generic Murdering Native Americans in 2018 and the plot of the story with the quadriplegic is both far too slight and far too cruel. I do like the last segment, which is typical darker Coen Brothers in that everyone thinks they have life figured out and of course, none of them do, and the story about the prospector is a gorgeously shot piece that throws more than one shocking turn at you.

But none of them are as good as the opening, which is absolutely immaculate and worth the rest of the movie alone. Tim Blake Nelson is perfectly cast as the titular Buster Scruggs, a baffling cartoon of a man who from frame one feels like if you crossed Bugs Bunny with Roy Rogers. He’s well-mannered, dressed all in white, a pleasant fellow and swell guy, who talks to his horse and sings while out on the range, and oh yeah if you fuck with him in any way, shape or form he will murder you in ways that will leave the Devil speechless.

It’s not just a Western, it’s every Western, as gritty hard men fall to a refugee from a singing cowboy movie (a subgenre that was incredibly numerous at one time, which feels as absurd as, say, an entire subgenre of superhero movies set in one universe.) People mourn the dead during a song-and-dance number, you can’t expect me not to love that. And then, the final twist: the antagonist from a “cowboy’s last ride” story comes on in, to usher Buster Scruggs and his hilariously cheap CGI wings off to Heaven, after Buster takes half a minute to realize someone’s blown his brains out. When the Coens set out to be funny, they are real funny, and Buster Scruggs is one of their funniest.

Why? I’m well aware of the problems inherent in having Blake Lively play the bisexual vamp Emily, whose sudden disappearance throws Anna Kendrick as Mommy blogger Stephanie into the middle of a web of dark intrigue. Sometimes being the villain isn’t good enough, and not enough depth is given her character to fully disentangle her sexuality from the web of lies she’s woven around herself, letting all Those notions about bi people creep in around the sides.

But what makes A Simple Favor work for me is this: it knows that it’s basically dropping a Mommy blogger into a Gillian Flynn novel and it leans right into it. This is a movie where dark foreboding strangers ask questions about interior decoration options, where two characters bond over the difficulties of motherhood even as they’re a minute away from trying to kill each other, where coded messages are delivered via a vlog about cookies, including one final entry that is absolutely hilarious.

It’s the most focused as a filmmaker that Paul Feig has been and it might be his best movie, if not necessarily his funniest – and the humor lets us laugh at the ridiculous situation that a sincere person has found themselves in. If I ever wind up pulled into a web of intrigue I hope to handle it as well as Stephanie did – or, if I have to be the one whose death set it all off, at least I can hope that I pull off a jacket with no shirt on as well as Emily did.

Why? Its disability politics are not that great – going by my understanding from people who have less mobility than I, treating a quadriplegic as someone who needs to be ‘fixed’ is offensive because it implies that life isn’t worth living with less mobility than fully abled people, so they need to be ‘made right’ or else be an object of pity.

But craftwise, Upgrade is a hell of a great actioner, the kind of old-school let’s-you-and-them-fight movie that doesn’t see much play in the age of the superhero. Logan Marshall-Green as Grey elevates the material, letting us know by simple body language when the chip in his body is steering him around, giving him full mobility as well as robot karate. The cinematography by Stephan Duscio is particularly noteworthy – once STEM takes over in a fight scene, the camera moves towards centering Grey (and STEM) and suddenly he looks like a video game character (which he kind of is.)

The story takes a lot of interesting twists and turns – what starts out as “what if we ‘fixed’ disability” turns into “oh, this has some problems” and from there, into an actual horror movie where if the characters involved with giving the main character had focused less on the miracle cure, all the bad stuff in the plot wouldn’t have happened. As disability politics go, there is that.

Why? Normally, Yorgos Lanthimos does not do a thing for me – his stiff dialogue, weird sex obsessions, harsh lighting and “whatever” approach to endings have put me off The Lobster and The Killing of a Sacred Deer. But sometimes the wrong kind of craft just needs the right kind of movie, and so: along comes The Favorite.

The Favorite is, above all else, utterly cynical about aristocracy. The noble courts of Queen Anne (played by Olivia Colman) are depicted with a bunch of men in powdered wigs watching ducks race. Someone comments on the fact that English mud always smells like shit. There is one of the world’s very few funny rape jokes in it, mostly because the butt of the joke is that aristocrats are scum. Queen Anne herself is falling apart in mind and body, to the point whoever sits closest to her is effectively the Queen – and the plot is all about two women (Emma Stone as Abigail, Rachel Weisz as Sarah) vying for her favor, knowing this full well.

It is also a great character study of each of its key players, all looking for power and/or love in some mixture or capacity, and none of them fully getting what they want because they’re all a little broken inside, either by life in general or life in the aristocracy in particular. It is also an extremely queer movie – Anne is queer, Sarah is queer, and Abigail either is queer or is willing to fake it ‘til she makes it. I finally found a Lanthimos movie I fully love. There’s hope for Paul Thomas Anderson yet!

Why? On the one hand, this is basically The Hateful Eight, but with mid-20th century Americana standing in for a blizzard. But on the other hand, Quentin Tarantino’s tics have gotten to the point where a movie that’s basically a Tarantino movie without them feels like a breath of fresh air. A version of The Hateful Eight where no one says the n-word feels like a hell of a step up to me.

It doesn’t have much of a moral, besides “what we do is who we become” – and even that’s a little shaky. But if this is nihilism, it is immaculately acted and shot nihilism – the warmth of the inside of the El Royale makes it always comforting to look at, and each chapter break gives us some new swerve or some new insight into the cast of characters so that we’re never fully on our toes. We’ve seen beefy Chris Hemsworth and we’ve seen funny Chris Hemsworth, but we’ve never seen dangerous, don’t-take-your-eyes-off-him Chris Hemsworth, and judging by this film, we ought to.

Bad Times at the El Royale is one of Drew Goddard’s few feature films, with him mostly focusing on his excellent sitcom The Good Place of late. This movie did not overall set the world on fire so it might be a while before his next feature – but when it comes, I’m very intrigued as to what it’ll be, if it’s anywhere as good as this one.

The “Well, I Wanted to Like It” List

Why? It’s not bad. It’s okay. But fandom told me it would be the single most queer movie of all time, and the most queer this movie gets is when She-Venom kisses Eddie Brock and the symbiote transfers over, and considering that in this shot we get a well-outlined look at She-Venom’s lovingly sculpted CGI ass and tits, I call into question just how queer this movie really is.

I’m tired of this Internet thing where a piece of fiction hints that maybe, if you do a handstand and squint and are really favorably inclined, two characters are queer, and fandom runs with it and acts like it’s plain as day – and meanwhile when actual queer fiction shows up, suddenly fandom can’t seem to run out of words to express just how many problems it has. It feels like we, collectively, are giving queerness points to the people who don’t deserve it – because if something is queer only in fandom, it can stay perfect, but if something is queer in the text, then it’s someone else’s less-than-perfect queerness and therefore it’s trash.

That’s not really a problem with the movie, so much as the reaction to it, but don’t worry, there’s plenty wrong with Venom on its own merits. A substantial subplot involves a symbiote breaking out, then circling half the world to get to… the place where the rest of the symbiotes are being held. The ending is another case of Hero Versus Dark Hero, as two blobs of taffy smack the shit out of each other. Tom Hardy’s acting feels like it’s trying for camp, and nothing is less camp than trying for camp.

It’s not bad, but it is not a tenth as good as it was hyped by fandom to be. Its Rotten Tomatoes score is lower than it deserves, but not that much lower.

Why? I wanted to like this so, so, so much. Pacific Rim, warts and all, is one of my favorite movies of all time, and I’m in full agreement with what my pal Tom Foss says: I either want there to be a new one every year, or just one great movie that stays great. I’m leaning a fair bit more towards that last one after this, however, because it just isn’t good.

The editing has so much chop – we awkwardly cut from Jake Pentacost running frantically towards an accident, and then we’re seeing the days-later results of that accident and there is no flow between the moments. The new jaegers have none of the memorable designs of the original group of misfits and lucky survivors; they did, however, recycle the name for the main robot, whose name sure sounds like a slur. (Here, here’s your better idea: the main jaeger is a refitted Coyote Tango and Jake Pentacost is now literally stepping into his father’s shoes.)

In contrast to the original’s mix of rookies, hotshots and vets, the new recruits all feel far too samey. The action lacks the impact of the original, where the tradeoff with the jaegers being slower is that every attack had the impact of a bomb. John Boyega is doing the best he can, and the script is technically solid, even if I feel that single-pilot jaegers are already messing around too much with the mandatory two-pilot-minimum that underpinned so much of the original’s themes. But otherwise, yeah: it is not a patch on the original.

This feels direct-to-video and not in a good way. Hopefully this was a result of them having too many ideas and pulling the movie in too many directions; I am holding out hope for the forthcoming anime. But sadly, not as much as I had before.

Why? As I mentioned earlier, this was a banner year for African American cinema, and this is a movie directed by and starring black women, and it was screwed sideways by the studio, and I went out of my way to see it and support it, because supporting black cinema shouldn’t stop with cinema about, and directed by, black cis men.

But Proud Mary is just, inert. Things just happen. One moment leads into the next and instead of it feeling like a well-directed concerto, it feels like someone is reading the notes off of a sheet of music. Danny Glover feels like he’s reading his lines off a cue card, and I know it’s not Glover losing his touch because he was excellent in Sorry to Bother You. It doesn’t have the impact of a serious crime story and it doesn’t have the energy of a more lighthearted romp. It just doesn’t work.

What a disappointment.

Why? Hoo, boy.

I enjoy Wes Anderson movies more than I don’t – in particular I think Grand Budapest Hotel is a wonderful film that’s utterly sure of itself and that Fantastic Mister Fox is one of the best stop-motion movies ever made. But this is a misfire and a half.

I don’t know why it’s set in Japan, beyond “it’s JAPAN!” I don’t know why it’s so inconsistent with its own conceits (the humans speak Japanese to keep us English speakers empathizing with the dogs? But then often the Japanese is translated or the humans speak English?) I barely remember the plot because every time a major plot point happened we say a zoom in on a sumo wrestler or a big gong and I groaned loud enough that I lost attention.

The dogs are all great, but they are standing on a very, very rickety scaffold of plotting and exoticism. And frankly, in an animated feature, “I liked the cartoon animals” is a pretty low bar to clear. Very skippable.

Why? God, I hate this movie.

It’s flabby and overstuffed, which would be less of a problem if the jokes were any good. But only about one-third of the jokes work, and of the ones that don’t, you have your pick of prison rape jokes, fat jokes, a dude-in-a-dress gag, and some sliiiiiiightly sketchy humor around Dopinder’s exaggerated accent. It takes the time to introduce a bunch of new characters just to kill them off, and not a one of them has a funny death – with the possible exception of Brad Pitt’s cameo, which is one second long.

The original Deadpool, rough as it was (I try to just sigh and move on when a movie makes a joke about a woman having a pecker) at least has a coherent plot, and knew when to ease off the yuks. This movie does not – it spends two hours building up to a conclusion for Cable and Deadpool’s arcs that is then completely undone in a series of crappy post-credits jokes. The plot stuffs Vanessa into a fridge and then the credits go “yeah, that’s pretty bad writing, huh” which is like telling me a joke about the fender bender that was your fault. I’m still gonna want you to pay for it.

Now in the interests of fairness: yes, Negasonic Teenage Warhead has a girlfriend in this movie, and yes, the aggressively no-homo MCU needs to get with the program toot-sweet. But this is also a movie where Deadpool gropes Colossus twice and it’s played as a gag, which tells you a lot about why TJ Miller is still around. On a related note, in one blink-and-you’ll-miss-it gag, there is a blurb on the news about Christopher Plummer not being in Deadpool 2, referring to the reshoots for All the Money in the World where Plummer took over for sex offender Kevin Spacey. Thanks for letting us know where you stand, movie.

They re-released this in the same year it came out, cut to be a PG-13 movie riffing on The Princess Bride, and I’ve seen literally no one talk about it – either everyone wised up in the past six months or everyone was just there for the katana stabs and the dick jokes. I can only hope that we are closer to the end of Peak Deadpool than we are to the beginning.

Honorable Mentions: Call me By Your Name, Crazy Rich Asians, Death of Stalin, First Reformed, Leave No Trace, Lu Over the Wall, Mandy, Won’t You Be My Neighbor, You Were Never Really Here

Haven’t Yet Seen: Solo, The Old Man and the Gun, If Beale Street Could Talk, Roma, Aquaman, Bumblebee, Assassination Nation

Leave a Reply