We live in the age of the pop culture revival, and the arrival of the eternal film and movie franchises, all born or borrowing from the model of superhero comics storytelling. Astro City, one of the most storied and beloved superhero comics of all time, went through a revival of its own in 2013, and that it came back as strong as ever was a miracle in and of itself. Over the course of a year, Charlotte Finn will be examining this miracle – all 52 issues – as she spends A Year in the Big City.

One of the most annoying thing as a writer is seeing someone else come up with a perfect idea and you feel like an imposter by virtue of not having thought of it.

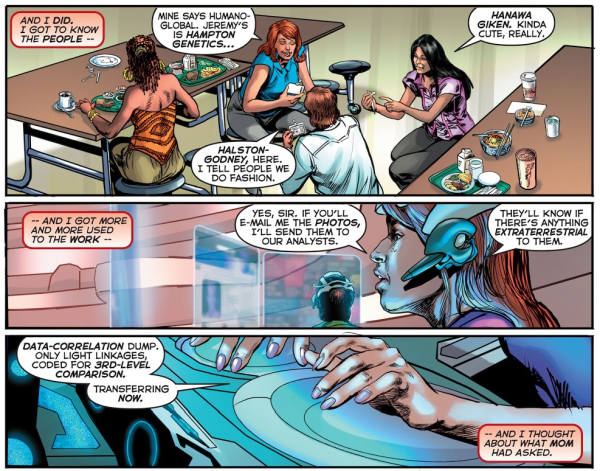

Issue #2 of Astro City (2013) opens with us meeting Marella Cowper, who is just another woman looking for a job. She gets a job at a call center, but because she lives in a superhero universe, it’s a call center for superheroes – handling emergencies in a world where “conquerors from a hollow earth” is on the drop-down menu.

There’s a famous Grant Morrison quote about how no one puts air in the Batmobile’s tires; that there’s only so much interrogation of the infrastructure of superheroics you can launch into before you’ve wandered away from the central point. It’s a nice quote, though a little unusual for a writer who once put himself in a fictional universe to get tortured on behalf of his self-insert character; if anyone would think that a fictional world should be solid all the way through, you’d think it would be him.

But it’s a good guiding principle for a certain kind of story for a certain kind of universe – the big shared universe where there’s no real consensus on where the fiction can go and what places it should avoid. Astro City isn’t a shared universe, though – it’s maintained by a handful of people. Astro City can ask “what’s the typical day of the person who does pump air in the Batmobile’s tires?” – and most of its best stories spring out of answering that question.

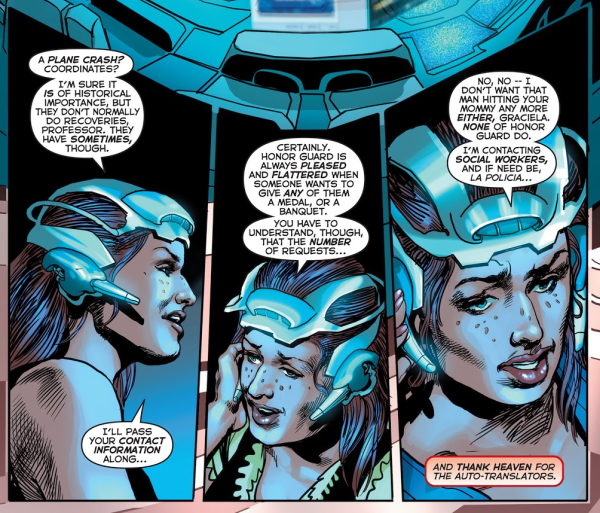

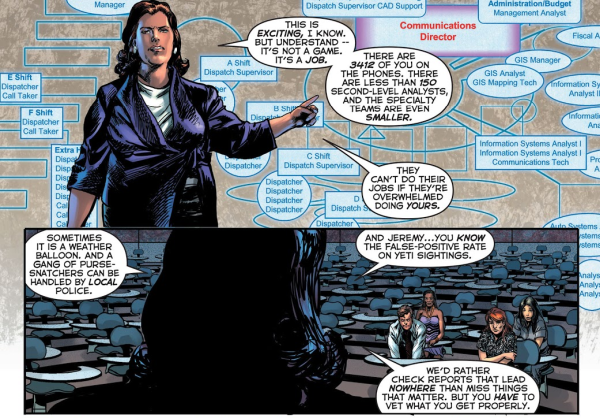

A call center for superheroes – emergency dispatch dialed up to Kirbytech proportions – is a genuinely great idea, and speaks to the aspirational aspects of the superhero. You may not be able to be Batman, but you could be adopted by Batman; you may not be able to join Honor Guard, but you can determine if their help is needed.

The story builds through montages and well-crafted setpieces towards its final cliffhanger page. Anderson is on point here, rendering a large number of talky scenes – a legendary challenge to draw – by dynamic figure arrangement, breaking up long sequences with the results of the calls the team fields, and arranging panels like this in a way that evokes a bank of monitors.

But if this job speaks to the aspirational aspects of the superhero, it also speaks to their blind spots. Marella and her coworkers do tap surveillance feeds, global satellite cameras, and a mountain of mined data to determine if something’s amiss, and it’s a reminder that we live in a society where all of that exists – and that, too, has been dialed up to Kirbytech proportions. While a critical aspect of the superhero is knowing good from bad and where and when you’re needed, there are shades of the surveillance state around it that can be disquieting if you think about it. If Superman can hear everything anyone in an entire city has to say, does that make him a one-man panopticon? Even if Superman can be trusted with that, can a group of fallible call center employees be trusted as well?

The story doesn’t go there – the aforementioned consensus of where a fictional universe can and cannot go remains intact – and the fact is, we do live in the era of Big Data and fiction is allowed to engage with the notion of living with that instead of changing that. Instead of an examination of the modern surveillance state, the story is about fallibility – about how, despite the importance of their work, the employees are only human, and the terrifying mirror to erroneously thinking “this looks like a job for Honor Guard” is thinking that something isn’t…

… and then it turns out, it was.

How Marella and her friends deal with this fallibility – and how fallibility fits into the superhero genre – is something we’ll examine in next weeks’ article. See you then!

Leave a Reply