We live in the age of the pop culture revival, and the arrival of the eternal film and movie franchises, all born or borrowing from the model of superhero comics storytelling. Astro City, one of the most storied and beloved superhero comics of all time, went through a revival of its own in 2013, and that it came back as strong as ever was a miracle in and of itself. Over the course of a year, Charlotte Finn will be examining this miracle – all 52 issues – as she spends A Year in the Big City.

They can’t all be perfect.

That sounds nastier than it is; there’s basically never been an issue of Astro City that’s out and out bad, especially considering the grading on the curve necessary for superhero comics out there. Whenever an issue leaves me a little flat, I remind myself that Wanted exists and got made into a movie, and my faith in humanity is diminished just long enough to be restored by Astro City.

All the same: sometimes an issue leaves me a little flat.

This issue, by the creative team of Kurt Busiek, Brent Anderson, Alex Sinclair, Kirsty Quinn and Comicraft (John G Roshell & Jimmy Betancourt) takes us back to the Broken Man, who is busy turning into an actual meme itself. (Grant Morrison would be proud.) Every time I look at his interdimensional map of “it’s all connected, man” I am weirdly endeared; he’s doing what a fan does, find connections across all the supposedly unconnected stories in a land of pure make-believe.

I have a weakness for well-done comics that talk to the reader, if only because badly done comics that talk to the reader are so, so common. (Looking at you, Deadpool. Yeah, I know you can see me too, you never shut up about it.) I feel the conceit is best when it’s either front and center, asking questions about the nature of reality and inviting the reader to become an active participant, or something that’s put on pause and allowing us to enjoy the story without being reminded it is a story.

The last few issues have been grounded in the real, but now we’re getting a few hints as to where it all fits in (whatever the Broken Man needs, it’s the kind of offbeat, quirky stories Astro City specializes in.) Astro City is a champion of the done-in-one, and this issue ups the ante to the two-and-a-half in one, one and a half of which is fine and the other, well.

First is a flashback to 1931, and the Blasphemy Boys, and if you like Tommy guns, zeppelins, and fedoras before they were ruined forever, are you ever in luck.

Alex Sinclair’s sepia tones, giving the impression of a faded photograph, illustrates the importance of a good color artist – as much as the slang, the fashion and the backgrounds work to establish this as the 1930s, it just wouldn’t feel the same if it were in the glowing hues of a modern superhero comic. The superhero hasn’t shown up yet – this is the era of the pulps.

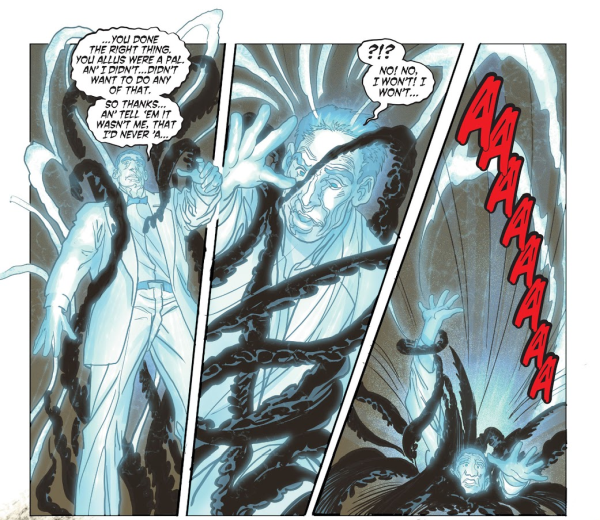

The Blasphemy Boys (with the one token white Blasphemy Girl) are on a case that goes wrong, that we’re shown just enough of to glimpse how wrong it’s gotten. A possessed member of the team guns down his teammates, has to be done in by his own commander, and most disturbingly of all, whatever possessed him isn’t done with him just because he’s dead:

One of the many things I find existentially horrifying is the notion of unearned damnation (damnation period, really, but there’s degrees to this.) The idea of dying, finding out that life persists after death, then finding out you’re condemned to Hell and your morality had nothing to do with it, is disturbing to contemplate. This is a horror story, sitting in the foundations that Astro City was built on, and it’s not resting in piece at all.

The Broken Man interrupts the reader, snapping back to his level of reality, but the reader’s attention drifts away again – this time, to a story about the cult of Lord Saampa, the Serpent’s Tongue, one of those cults that shows up in superhero comics where there needs to be a lot of cannon fodder we don’t feel too bad about the heroes beating up. The conceit of this story is that it’s really cut short, in mid-panel…

… in a fantastic page from Anderson, existing on two different levels, and subconsciously evoking one of the most famous pages in history, a page all bound up in the notion of “literally everything being at stake.”

The last page of his first appearance establishes the Broken Man as an unreliable narrator, but this reinforces that he may in fact be a hostile narrator – there are things he doesn’t want us to see, possibly for our own good. He chastises the reader, then decides that since we want a complete story, he goes and gives us one with eight pages to go.

This story is a flashback to the turn of the century, with the heroine Dame Progress tangling with Mister Cakewalk, and… well.

Now, I don’t really hate Mister Cakewalk – as the series progresses, he turns out to be an interesting character with an interesting driving theme. And I’m not an expert on turn-of-the-century African-American Vernacular English so maybe it’s all period-accurate. Whether or not it needs to be is another story – even if it fits the era it’s set in, I’m reading it in the era of right now, and historically English has been based around a lot of racism that a modern viewer doesn’t necessarily need. But there’s a case for dialect that fits the times it’s set in.

However, when it comes to accents and vernacular in comics, it’s like calling a song you wrote a “rock ballad” – if you’re going to do it, you better be damn sure. Miss the mark by even a little and it can lapse into caricature, and caricature of a group of people leads nowhere pleasant. Superhero comics, in particular, have a long history of having caricatures of marginalized groups as the only representation that those groups have, and while this might be a commentary on that thing, there’s a thin line between satire of the thing and just doing the thing.

Astro City is and always has been a very diverse universe, even though it centers around an American superhero city, so I don’t think this is ill-intended. I just don’t think that the vernacular hits the bullseye it needs to in order to cleanly set itself apart from caricature, and without that bulleye it’s not what it could have been.

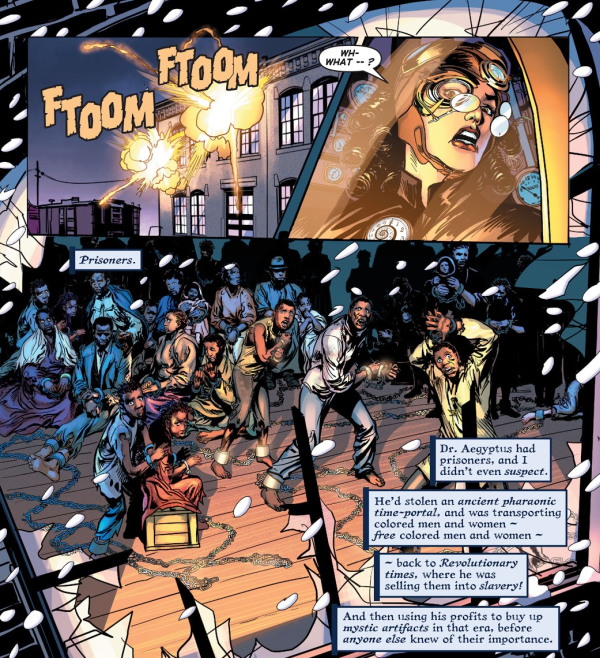

That said, what Mister Cakewalk is, is a great idea – the anti-villain, the sympathetic rogue, but applied to the kind of heroics you get at the turn of the century; the antagonist who has something of a point. Because his duel with Dame Progress leads to her discovery of this:

In the introduction to the first volume of Astro City, Kurt Busiek comments that if the superhero serves as a metaphor for male adolescent power fantasy by default, can the superhero serve as a metaphor for more than that? The conflict between Dame Progress and Mister Cakewalk serves this extremely well.

Dame Progress is about helicopter jetpacks and steampunk walkers and glasses with a lot of lenses in them – the progress of industry and technology. But industry, especially in America, has a long and sordid history of exploitation and slavery, especially of black people. One of the most persistent criticisms of steampunk is how it ignores all this in favor of “let’s stick some gears on a corset” and never grapples with the undertones of what it’s glamorizing.

Mister Cakewalk literally forces Dame Progress to see what she was blind to – that the miracle of something like time travel is only a miracle to the people who control it. If time travel means the past is never truly over, then that means that its sins are never truly gone either. It’s only a nice place to visit if you’re welcome there – if it’s not, then all it is, is another means of exploitation.

Mister Cakewalk makes himself scarce, to show up again in later comics – for a later time. Next week, it’s back to the mystery of the open space door from space, and a story that asks about the nature of ambition and contentment. See you then!

Leave a Reply