(Writer’s Note: this is a reproduction of an essay I posted to Tumblr some years back. It has been republished on this site, as close to the original as possible, for easy archiving and reading.)

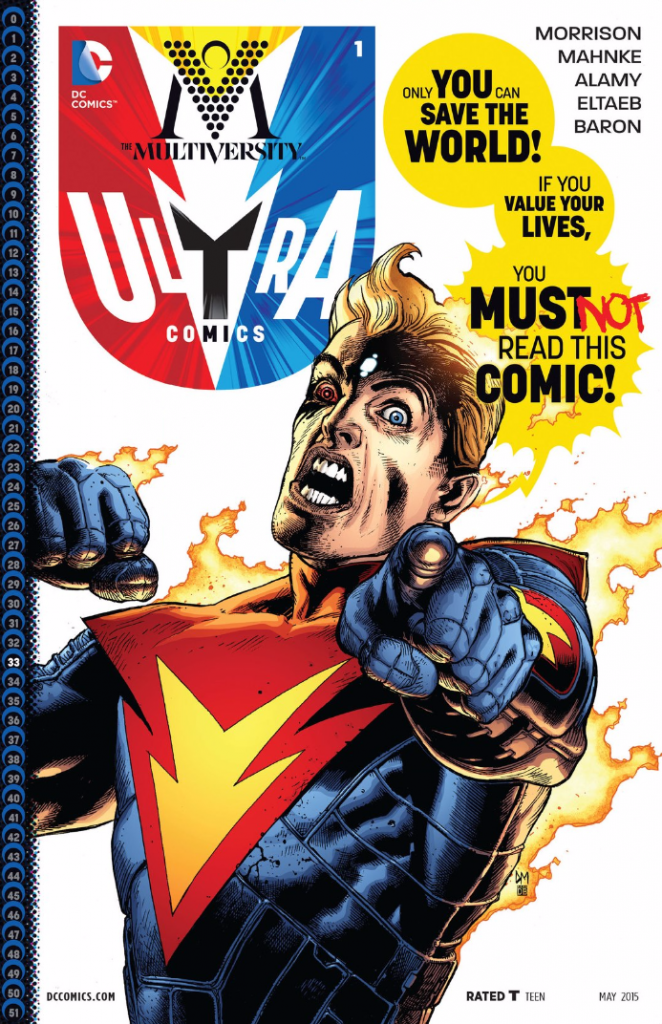

Ultra Comics #1

Grant Morrison: Writer

Doug Mahnke: Penciller

Christian Alamy, Mark Irwin, Keith Champagne, Jaime Medoza: Inkers

Gabe Eltaeb, David Baron: Colorists

Steve Wands: Letterer

The recently concluded Multiversity event from Grant Morrison and a host of terrific artists doesn’t fully work for me, sadly. But it gave us Ultra Comics, so it was all worth it.

It doesn’t fully work for me because there is a keen sense of “been there and done that” with the bookends, which are where the story’s meat is found. Nix Utoan waking up in a mundane situation – his secret identity – on the final page is about a beat-for-beat remake of Final Crisis, and the format itself is evocative of Seven Soldiers, though not nearly as long and with a sense of missed connections in the final act. It’s difficult for anyone to have worked in comics as long as Grant Morrison has and not found themselves repeating their tics, of course, but it’s still a flaw – and repetition, by its nature, negates the kind of mind-expanding writing and mad-idea rush that drew me to him. In the wake of its absence, I have to look to the rest, and it’s there that Morrison’s more questionable tics are prevalent (his dialogue can be a little tin-eared and his pacing sometimes doesn’t always sync well with the page turn.)

Its central conflict of the superheroes versus, essentially, gentrification – outside forces moving in and paving over the old culture with their own – works somewhat better, but only somewhat. The conflict lies between damaging new ideas (such as a warped idea of what adulthood means, or an unexamined fidelity to “realism”) represented by the Gentry, versus positive new ideas (more women, more LGBTQIA people, more people of color) represented by Operation Justice Incarnate and the multiversity (or, “multiverse diversity.”)

But the worlds aren’t that diverse – mostly remixes of pre-existing ideas slotted into the familiar roles of the JLA or the Avengers. Here’s Etrigan, but on this world he’s the analogue for Superman. Here’s Superchief, but on this world he’s an analogue for Superman. It feels like a wave of gentrification, of imprinting not just the superhero but very specific analogues for very specific superheroes, has swept through the multiverse already. It’s a battle that in some ways was lost before the series even started.

(from The Multiversity Guidebook. Art by Yildiray Cinar, Dave McCrag, Todd Nauck, and Gabe Eltrab)

Bringing in a more diverse array of takes on various superheroes is far more welcome – Calvin Ellis as Super-President is one of those just-dorky-enough-to-work comics ideas – but it’s hampered by keeping them all walled off on different Earths, which Grant Morrison may be the only one writing about and he’s just one dude. A world where the majority of the superheroes are women sounds super-cool, but if we hardly ever see it, is it really that big a step forward?

If this was the Grant Morrison Expanded Universe – the GMoEU – owned 100% by Morrison and his collaborators, I could see us returning, again and again, to these characters and their adventures. But the wagon is hitched to DC Comics, which is a bureaucracy bigger than any one person and which makes decisions that often feel like they were decided via dartboard, as any organization with internal politics and a raft of management often does. Without the corporation’s commitment, the idea is sadly doomed from the start.

(FAKE EDIT: I’ve been informed since I started writing this essay that the Multiversity does show up at the end of Convergence, an appearance I’ll take people’s word for. So the company may be more committed to it than I thought.)

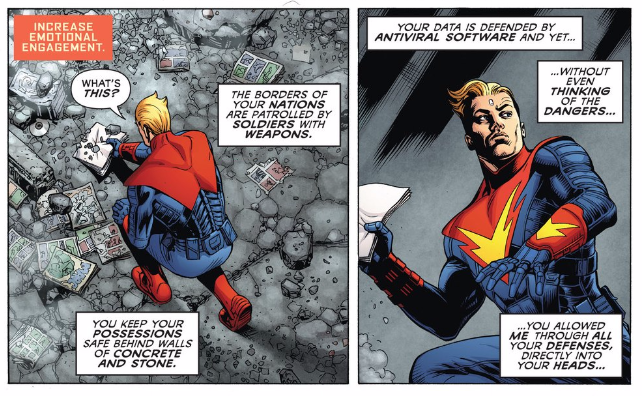

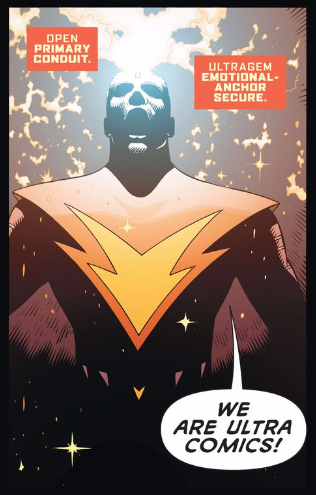

All of this comes to a head in the pages of Ultra Comics. The premise of Ultra Comics is that on our world, the only superheroes that can exist are fictional ones, so one’s been created to protect us, and its protection manifests by us by reading this comic. Doug Mahnke is the perfect artist for this conceit, since Mahnke’s art has the thick shadows, aided with Christian Alamy, Mark Irwin, Keith Champagne, and Jaime Medoza’s inks, that are code for “realism in comics” – but he also has the storytelling chops and the classic dynamic figures that say “superhero story,” aided by Gabe Eltaeb and David Baron on colors. Mahnke can also get disturbing as hell, and this is a horror story. Specifically, a horror story aimed at three different groups of people.

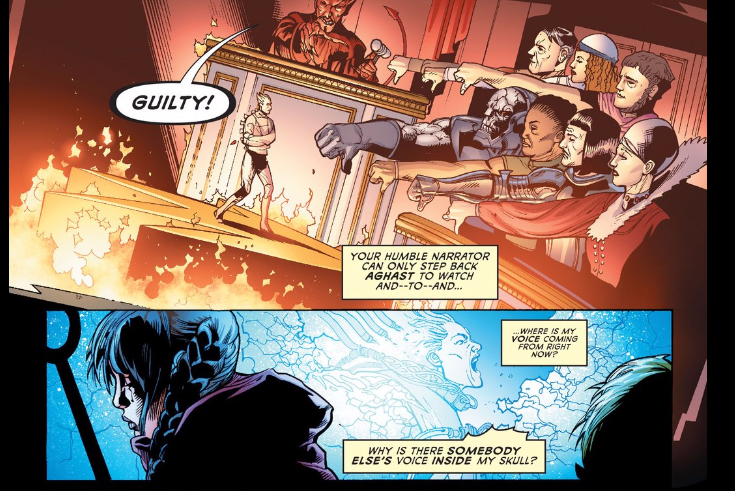

The first group is fictional characters – specifically, fictional superheroes in the Multiversity. Everyone who reads an issue of Ultra Comics throughout the various issues of the series comes away changed for the experience, because all throughout the comic is page after page of pointed deconstruction of the superhero, starting with the hard truth that superheroes aren’t real.

Ultra Comics, the title character, knows that Ultra Comics isn’t fully alive, and the idea seems to cause the hero to falter. Upon emergence into the world where Ultra Comics’ first mission will take place, our hero soars into the sky majestically, and then expresses doubt about the very notion of good guys versus bad guys.

In discussions with my friend Tom Foss on Twitter, we keep coming back to the notion that the superhero needs some method of knowing right from wrong, since that’s the only thing that makes an unaccountable vigilante work. The sense of capital-J Justice that Tegan O’Neil also writes about here. Superman has super-senses; Wonder Woman has a lasso that literally compels truth; Batman is the world’s greatest detective. Once you can tell the good guys from the bad guys, you can punch the snot out of the bad guys and mock-dust your hands and it’s another triumph for our hero, in contrast to the muddle that is trying to make your way in the real world’s morality spectrum. If Ultra Comics can’t do that – if Ultra Comics, in fact, casts doubt on the very idea – then suddenly this superhero’s not really the superhero as we know it any more.

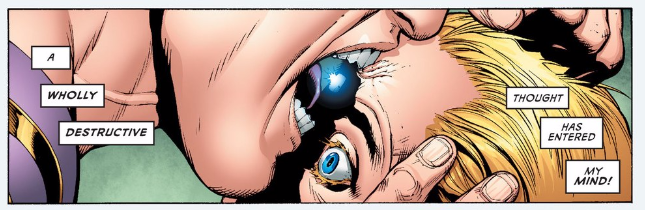

There is a creeping doubt in the back of Ultra’s mind, via the omnipresent narrator, chipping away at Ultra Comics’ certainty of right and wrong and Ultra’s confidence in winning. The core idea of psychological warfare is that the moment you’ve won any conflict is when the enemy has been convinced that they have lost. What Ultra Comics is designed to do to superheroes is put this hostile independent thoughtform – what the comic calls a HIT – into a superhero’s head.

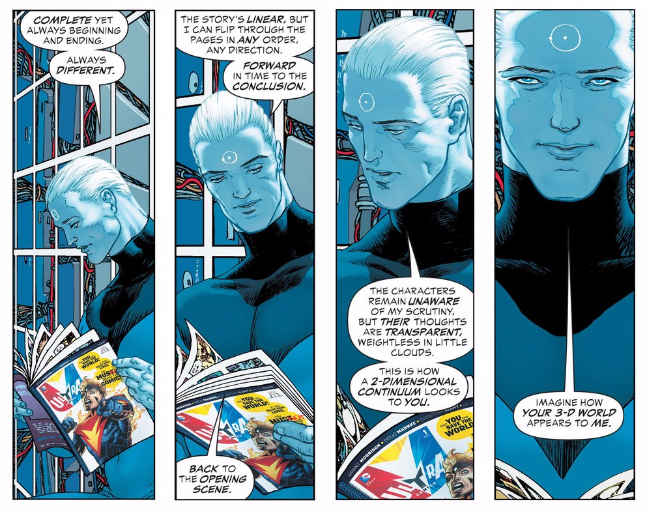

Upon capture and reveal of the villain, Ultra Comics tries not one, but two patented “there’s a slim chance this’ll work” final gambits: revealing a heretofore unknown property of the ultragem that gives Ultra Comics superpowers, and revealing that Ultra Comics can travel backwards and forwards in the pages of this comic. Standard stuff – we’ve seen it in a hundred comics and a dozen movies, and I pump my fist every time. But here: none of it works. The message of all of this is that your tactics cannot stop the Gentry; they have been anticipated and accounted for. It’s like propaganda written by monsters from Hell.

Imagine you’re a superhero in one of the worlds of the Multiversity, and you pick this up. It’s a story about someone like you, saving the world and making things better, except that in the course of trying to make things better they wind up making things worse. That has to eat at your confidence, and if you’re the type of character in a job where you save the world every third weekend, a loss of confidence is devastating.

(art by Cameron Stewart) In The Society of Super-Heroes, Al Pratt gives up on traditional superhero morality and kills a man. And it’s blood sacrifice – not by Al, but by another – that dooms his world.

(art by Frank Quitely) In Pax Americana, Captain Atom disappears from the universe after reading Ultra Comics, and without him, the President’s entire plan and quest for absolution isn’t going to work.

(art by Ben Oliver) In The Just, Kyle Rayner is given vicious flashbacks, Megamorpho commits suicide, and Alexis Luthor is revealed to be her father’s daughter after all.

Interestingly, it doesn’t seem to show up anywhere in Mastermen – in that world, the Gentry saps Overman’s confidence directly, via the dreams he’s subjected to. Or maybe the world has already fallen to rot and the Gentry have already won. It’s also seemingly absent from Thunderworld, which is the world that rejects the Gentry the most thoroughly – weird serial killer Sivana and the rotten beauty politics of Georgia Sivana aside.

The conceit of The Multiversity is that what is fake in one universe is real in another – that all stories are true. The conceit of Ultra Comics is, what if that could be weaponized against superheroes? What if a comic – a derided art form, even amongst its fans, dismissed as just dumb bullshit, and therefore the perfect surprise attack – could penetrate the mind, where bullets and bombs merely bounce off the body, and sap a superhero’s greatest power?

The thing is, the poison thoughts in Ultra Comics that bring down superheroes are just normal thoughts in ours. Of course morality is complex. Of course sometimes our last minute gamble doesn’t work out. Of course sometimes we’re going to lose. These things are just a part of life. What this leg of the comic’s thesis is postulating is that what is part of our life is death to a superhero; that when we bring realistic things into their universe, we’re touching the wings of a butterfly. Even if our intentions are noble – even if we just wanted to touch something beautiful – just by touching them, we ruin them, and both butterfly and superhero will never fly straight again.

That’s one way the door swings: the notion that’s what normal in our universe is poisonous in theirs. But the door also swings back out of the superhero universe, into ours.

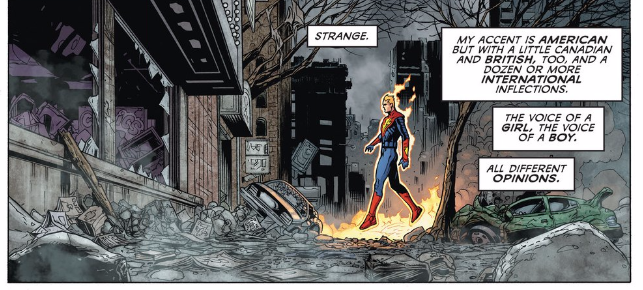

Ultra Comics, the character, is meant to be a superhero powered by us, the reader. Ultra Comics is meant to be a character that we bond with and empathize with. Ultra’s designed that way, and the word really is “designed.”

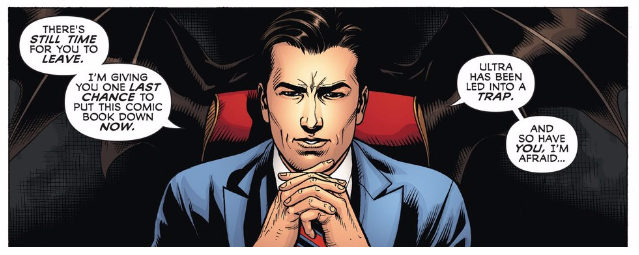

Ultra Comics is put together by a team that we know nothing about, beyond the fact that they’re called “memesmiths.” The team is led by a man in a suit that turns out to be nefarious, killing off the team that creates Ultra Comics as soon as their hero is out there in the middle of a story. I can’t help but think about how many people thrill to the adventures of a superhero without knowing fact one about the people who create them, and how easily these creators are swapped out if they threaten the intended goals of the owners of what they create.

Of course, blaming the person being misled is pointless – they’re not the problem. The problem is the people doing the misleading, behind closed curtains that Ultra Comics throws open wide.

The notion that Ultra Comics is designed, rather than created, extends to Ultra Comics’ four morality settings – all stuff we’ve seen before, all safe bets, all stuff an executive at a corporation would settle on out of sheer creative inertia. It extends to Ultra Comics’ interior monologue, which switches from thought balloons to narrative captions for no reason other than it’s the current trend. Said internal monologue, we’re told, represents all of us, and is a mix of all our voices.

But Ultra Comics isn’t all of us – or rather, Ultra Comics is all of us, as long as “all of us” happen to be cisgender white guys with blond hair, blue eyes, and a ripped physique. I don’t hear my voice in my head when I read Ultra Comics’ thought balloons; I hear a man’s voice, since to me, Ultra Comics is a man. And while I feel I ought to relate just fine with people who are different than me since that’s a bedrock foundation of social progressivism, sympathy and empathy aren’t the same thing. I can sympathize with Ultra Comics more easily than I can empathize. Ultra Comics is not me.

By stating that Ultra Comics is all of us, whether by design or by choice, the narrator is stating that we should be like Ultra Comics – that the way Ultra Comics looks is the default setting for the human race. If you’re not like Ultra Comics, there is something the matter with you. And that’s insidious. That’s erasing. That reduces the colorful spectrum of humanity to a single notion of what’s proper.

We, out in our world, have our poison thoughts, our HITs, to deal with too, dating back long before I was born, so ever-present they may as well be invisible. The idea that gender is essentialist and that one gender should be positioned above another. The idea that only white people count as human, and that all other races are base and lower. That having no children is wasteful, and that loving any gender other than the widely accepted one is sinful. That you need to look a certain way. That you need to think a certain way.

Ultra Comics does not want to embody any of these thoughts; Ultra Comics believes, honest and true, that Ultra Comics was built to protect us all from the poison thoughts that the Gentry use to conquer worlds. But you can hurt someone without meaning to. You can pass the poison along unthinkingly. You can touch a butterfly’s wings without knowing what’ll happen.

Ultra Comics proceeds into battle against the forces of evil. Ultra Comics confronts an army of bugs dressed like superheroes and spouting the same lines over and over – the innate repetition of the monthly superhero made manifest, and Ultra Comics bursts onto the scene brandishing Ultra Comics’ own shopworn lines and maneuvers. Even the girl Ultra Comics meets repeats herself just like the Crawlies do.

As last-minute superheroics fail and as ethical codes call short, Ultra Comics stares out the page as Ultra Comics realizes the truth, begging us not to turn the page. Ultra Comics was sent to protect us from a hostile independent thought-form, and that thought-form represents invasion followed by conformity in service to the invaders. To make the gentrified more like the invaders, even if there’s no way they can ever be, any more than there’s any way a black man can be white. A gentrification driven by a profit motive, as surely as the test-marketed corporate design of a superhero is – the same superhero that we just spent the past several minutes letting into our minds.

Ultra Comics cannot protect us from the Gentry, because Ultra Comics is the Gentry.

Even if Ultra Comics had succeeded and flown off to many more glorious adventures, Ultra Comics would still be who Ultra Comics is: created by committee, reeking of lowest-common-denominator corporate thinking, white, male, cisgender, classically handsome, and probably straight (though just as likely to embody a pre-pubescent mindset that girls are icky, which is also bad.) The thoughts that poisoned the superheroes in the aforementioned comics of the Multiversity would be absent, but the thoughts that poison us would continue. Ultra Comics, from issue #2 onwards, would be our problematic fave.

That’s the second way the door of Ultra Comics swings. But I think there’s a third way that Ultra Comics is a horror story, buried underneath the other two. I think Ultra Comics is a horror story Grant Morrison is telling to himself.

All throughout the story, reference is made to “the Oblivion Machine.” It is something that Ultra Comics says “we’re all trapped inside.” Ultra stares right out at the reader as this is declared.

Or rather: Ultra Comics stares out the page at the artist. And the writer. And everyone who worked on the comic before we saw it.

We hear that the Oblivion Machine eats our time – wastes our time – and it makes a clear reference to entertainment and fiction, which is what this comic is. I believe that the Oblivion Machine can mean many things and is open to many interpretations, and that one of those interpretations is that it represents the fear that we’re all wasting our time with this fiction stuff.

Grant Morrison is one of those magic-of-stories authors, and there’s something to be said for that. (We all like to mock Neil Gaiman for it, but Terry Pratchett was basically the same way, and I’ll be damned if you say anything bad about him.) The premise of the “we want diverse representation in our entertainment” movement – which Multiversity is part of, with the bookends at least – is that what we read, watch, and play does matter and help shape our opinion of the world. Without the notion that storytelling matters, a whole lot of the progressive side of fandom starts looking really stupid.

The mirror side of how far a story can lift the human soul, is how far down it can crush it, which leads to the key premise of “be careful of what you send into a mind” – the natural complement to Multiversity’s message of “be careful of what you let into your mind.” Creatives do have a responsibility to consider carefully what message that their fiction sends, because fiction inevitably does send a message.

But fiction, by its nature, allows for more than one reading, more than one interpretation, and by extension, more than one message. People come out of movies all the time with an entirely different reading than the one I take in. People write “the bad guy: maybe they’re the GOOD GUY????” articles constantly, and there is no stark illustration of which perspective fiction is trying to impart than designating one perspective as the one the baddies have.

The good guys can clearly tell us not to turn the page…

… and the bad guys can order us to turn the page…

… and we’ll still turn the page, even though the story – and behind it, the creators – is telling us what will happen.

Even this very piece that I’m writing right now, and that you’re reading at a different kind of right now, where I’m pulling out interpretations that Grant Morrison and Doug Mahnke probably didn’t intend, gives weight to this notion. Grant Morrison and Doug Mahnke could probably let me know that this isn’t what they intended, but I don’t know them and they’re not here. Unlike environments where a lesson actually is formally taught, such as a lecture hall or a classroom, there’s no peer review. There’s no test. There’s no professor to let me know if I’ve disappeared into my own head and my interpretation is actually in the text or is just shadows on the cave walls of my mind that the light of the story brought into relief.

The creators can inspire without meaning to, and crush the soul without intending to. The work can reach people the creators have never met and never will, lingering long after the creators are dead, like background radiation that just won’t go away. (Ultra Comics specifically alludes to the cross-time nature of its empathic connection with the protagonist, which is how the poison thoughts get in.) The creators may not intend harm, but again: you can pass on poison without meaning to. You can touch a butterfly’s wings without knowing what’ll happen.

The natural response is “cultural critique” – being aware of what you’re reading, playing or watching, and being aware that it contains poison thoughts. If fiction needs cultural critique to decipher its real message, it’s probably not that great at clearly communicating it in the first place – but ignoring that, cultural critique is used as a weapon against the Gentry’s HITs…

… and it doesn’t work, either. Knowing that there’s rat poison in your Cheerios doesn’t protect you when you eat them. And even if there’s an effective antidote on hand, you could just not eat rat poison in the first place.

Of course, fiction can elevate by accident in addition to harming by accident, but the thing is, society judges us more harshly by the one thing we did wrong than it elevates us over the twenty things we did right, and for a good reason. You’re supposed to not hurt anyone. That’s the default setting of life and society. Deviations from that norm need justification, and if fiction causes harm, there’s a good case to be made that it needs justification also. You can say that it’s an accident and not part of the creator’s intent, but in assessing fiction, we are often taught to disregard creator intent entirely. We even have a term for it.

So taken together, a creative person can cause harm, without meaning to, even if it goes against their stated intent and their own interpretation of their own work. They can do this to someone they’ve never met and will never meet, across vast distances of time and space. All fiction is a potential, and accidental, delivery system for a HIT. In this interpretation, the power of fiction is real, and it is not just uncontrolled, it is uncontrollable. You can’t decide what happens after the story goes out into the world, no matter how much you plan. You have no control over its capacity to cause harm.

If you tell stories for a living, and if you genuinely do not want to cause anyone harm: that’s a scary thought to let into your own head.

So Ultra Comics is about the fear of unintentional consequences, be they consequences of a message you let into your own head, or the consequences of one you put into someone else’s. Earlier in this piece, I wrote about how one of the pillars that makes the superhero work is knowing what the right thing is, and being able to do it. Know what’s good or bad in clear, concise terms, and then punch the bad until it promises to stop being bad. By causing harm, even by accident, Ultra Comics illustrates that another of those pillars is control – being able to hit the baddies, and only the baddies.

If you introduce the notion of accidental, unintentional harm into that, and then imply that the harm is real regardless of whether it was intended, and that it can’t be undone – that undercuts the notion of the superhero, and casts serious doubts on whether fiction’s transformative power is a good thing. You’d have to dig hard to find a deeper fear of people who just want to bring more good into the world – be they superheroes, the people who read them, or the people who write them.

Or maybe I’m just jumping at cave shadows, and it’s just a silly comic book.

Thanks for reading. Don’̦̘t͉̖̻̜͉̘̤͟ ͔c͕̹͖ͅl̖̲̰̗̱o̝͚̥̤̲͔ͅs͈̮̲̫̝̫͍e͍̠̣̗̕ ̻̺̠͞t̵̪ḩ͍è̥͉̙̮ ͎̯̰͔t͇a̙̬͠b̮͉ͅ.͓͙̠̦̀

Leave a Reply